Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki enjoys worldwide reputation — and for a reason. His works are perceived as anime per se and need no advertising or special introduction. For many Miyazaki is a wise and kind storyteller, whose oeuvres are equally close to both children and adults. However, the great master works with historical material as well, sometimes taking up serious and dark matters. This article is about one of Miyazaki’s most peculiar creations, his historical dieselpunk Porco Rosso.

Dreams of the Flight

Miyazaki’s affection for the sky and aviation is well known — in fact, it would be safe to say that it has been embedded into his image. The future animator’ father managed a company that produced parts for Japanese warplanes during World War II (specifically for the A6M Zero fighter) — this may have contributed to his son’s pursuits and passions. Incidentally, the history of the Zero fighter jet and the biography of its chief designer, Jiro Horikoshi, became the basis for Miyazaki’s feature The Wind Rises (2013).

In 1982, Miyazaki began publishing the manga titled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which was adapted to a feature film in 1984. It is often believed to have heralded the heyday of the author’s creative work and marked the onset of Miyazaki’s fame as an independent director and screenwriter. An essential feature of the animator’s unique style showcased in the film was the abundant imagery of diverse fictional aircraft and aerial combat scenes. The humanistic and anti-war components that Miyazaki incorporated into the plot of that manga would later become his trademark themes.

In 1985, Miyazaki together with a team of his colleagues founded his own animation studio, Studio Ghibli. Its unconventional name, Ghibli, was borrowed from the Italian World War II-era multipurpose Caproni Ca.309 aircraft nicknamed Ghibli after the wind that blows in the deserts of Libya. The first film Miyazaki produced in his new studio, Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), entertained audiences with amazing adventures in the air. Unlike Nausicaä, a “pure” sci-fi work, this feature had a dieselpunk spirit in it, and the world shown in the film resembled Europe of the early 20th century. The picture delivered a very strong anti-militarist message, and the chief villains were cruel and greedy military men.

Miyazaki’s following Studio Ghibli productions were less dramatic and changed their target audiences to families and children. The moralizing environmental fairytale about a kind-hearted forest spirit My Neighbor Totoro (1988) was nowhere near aviation, but a good portion of Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), a feature that few would call a movie for kids, telling the life story of a young witch in a world similar to Europe of the mid-20th century, was reserved for flights. Both pictures not only cemented the director’s reputation, but also played the pivotal role in the evolution of his image of a wise kind storyteller.

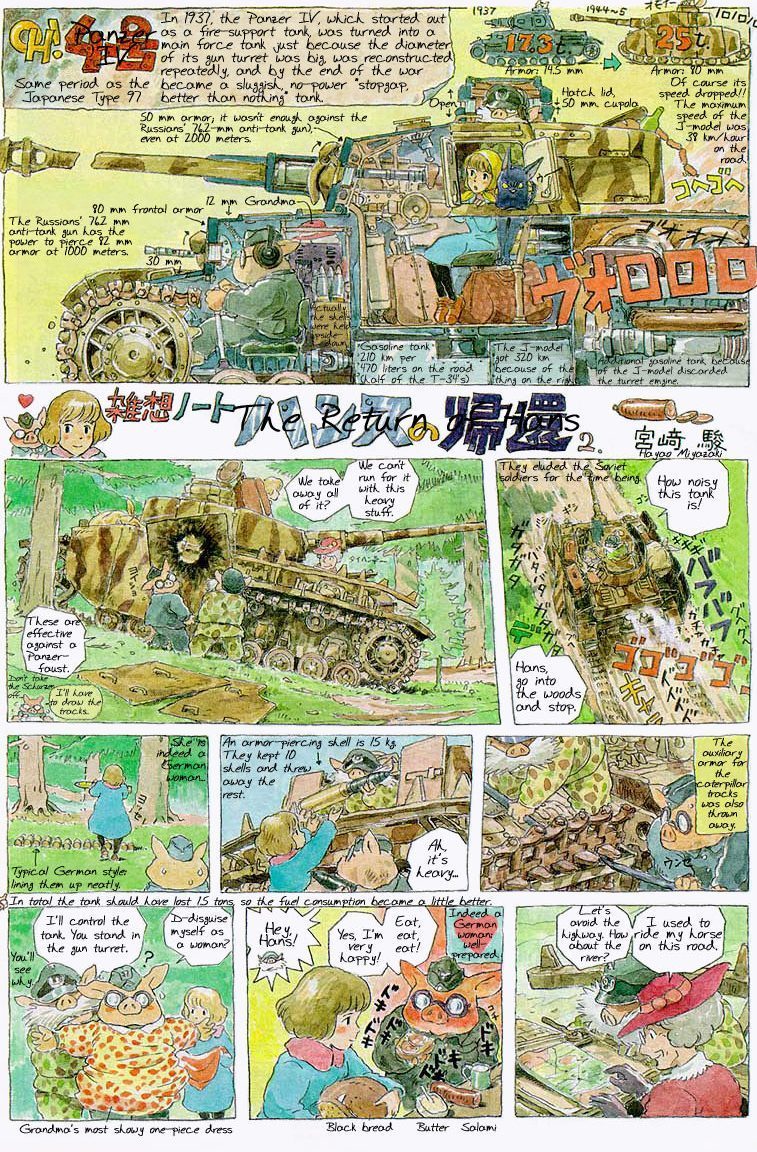

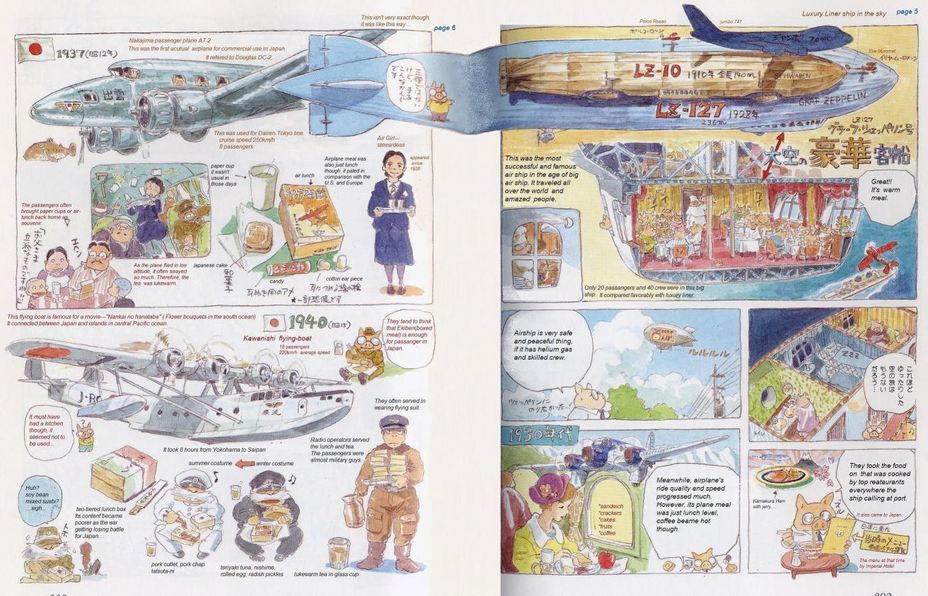

Manga was a much less visible aspect of Miyazaki’s creativity in the 1980s. He started working on historical comic books in 1984, which later formed a collection with the simple title Hayao Miyazaki’s Daydream Data Notes (Miyazaki Hayao no Zasso noto). The Notes were brief graphic stories dealing mainly with military history and technology of the early 20th century. Serious issues were presented in an ironic way. Those works never fit the image of the good storyteller well, yet they became the source of inspiration for the master’s next film, a most unusual one in his long career.

The Age of the Flying Boat

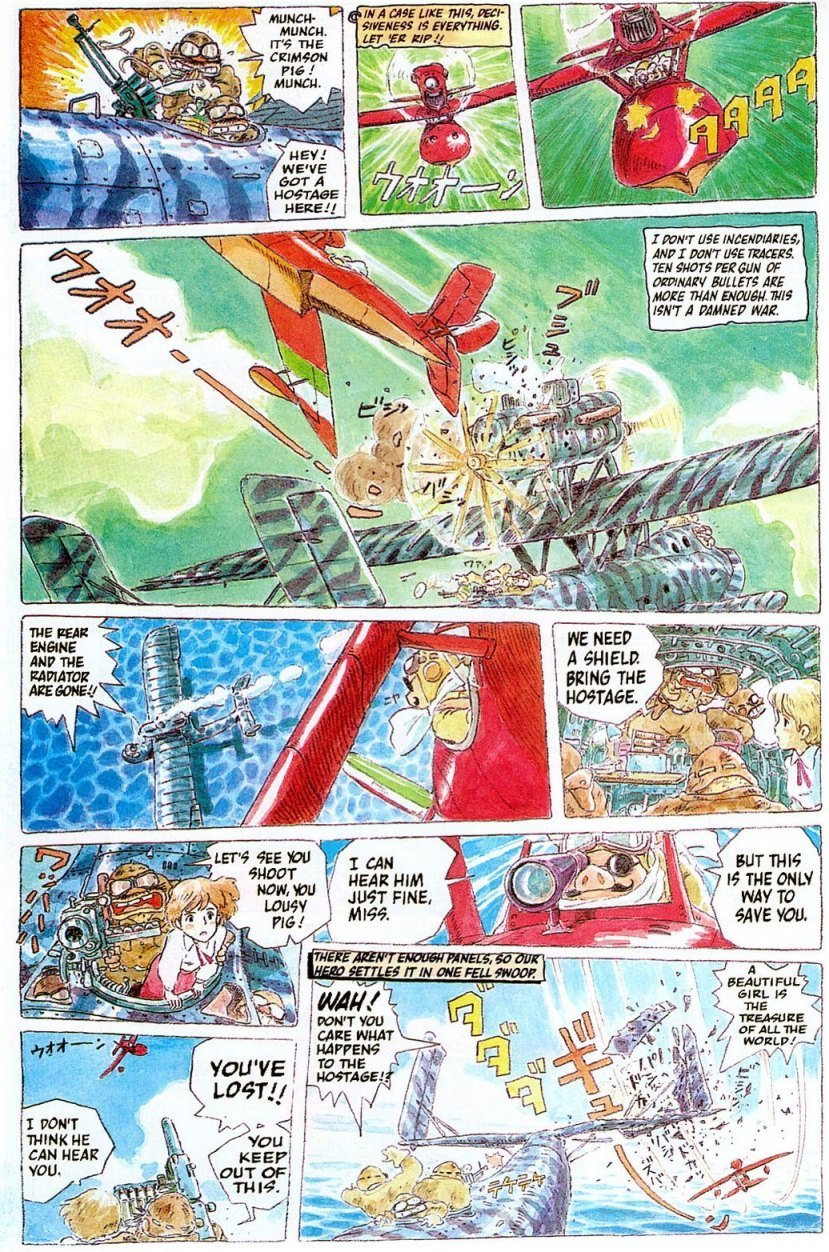

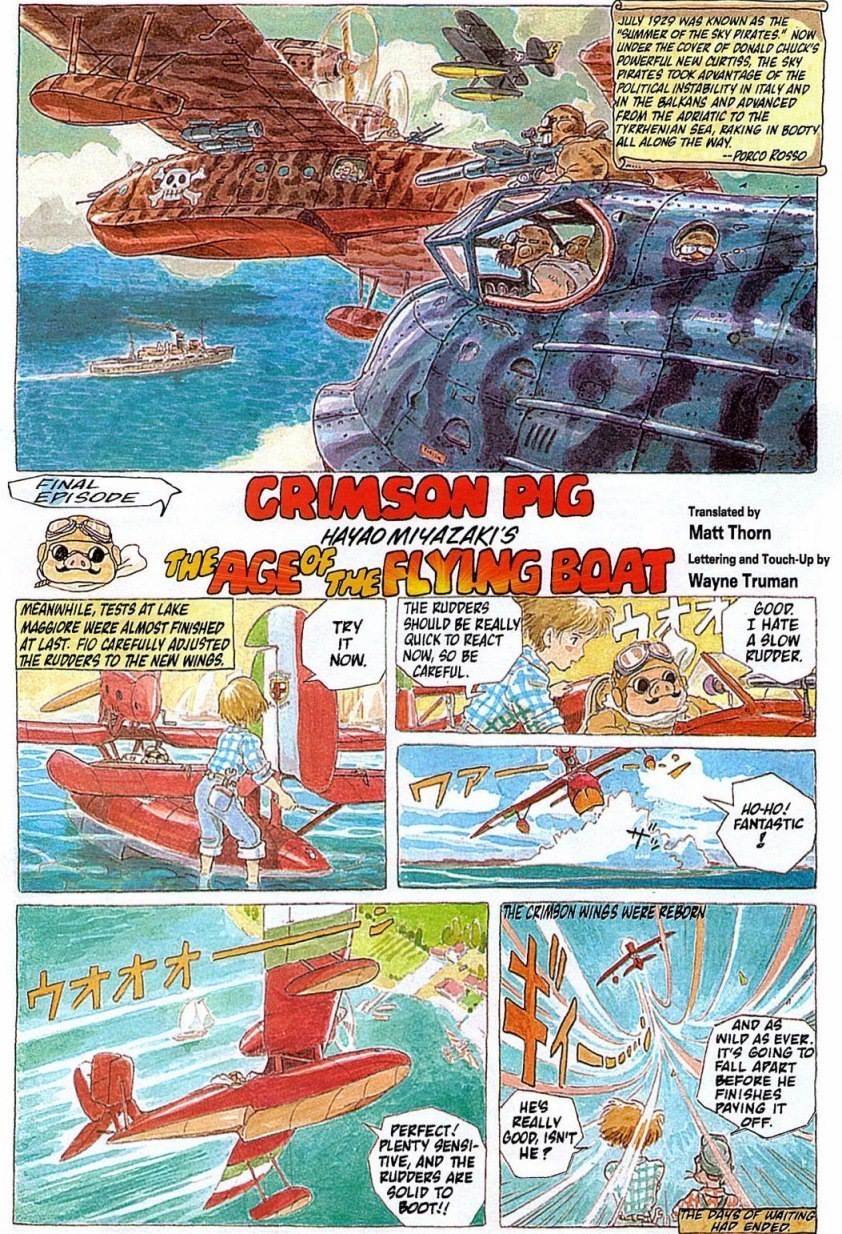

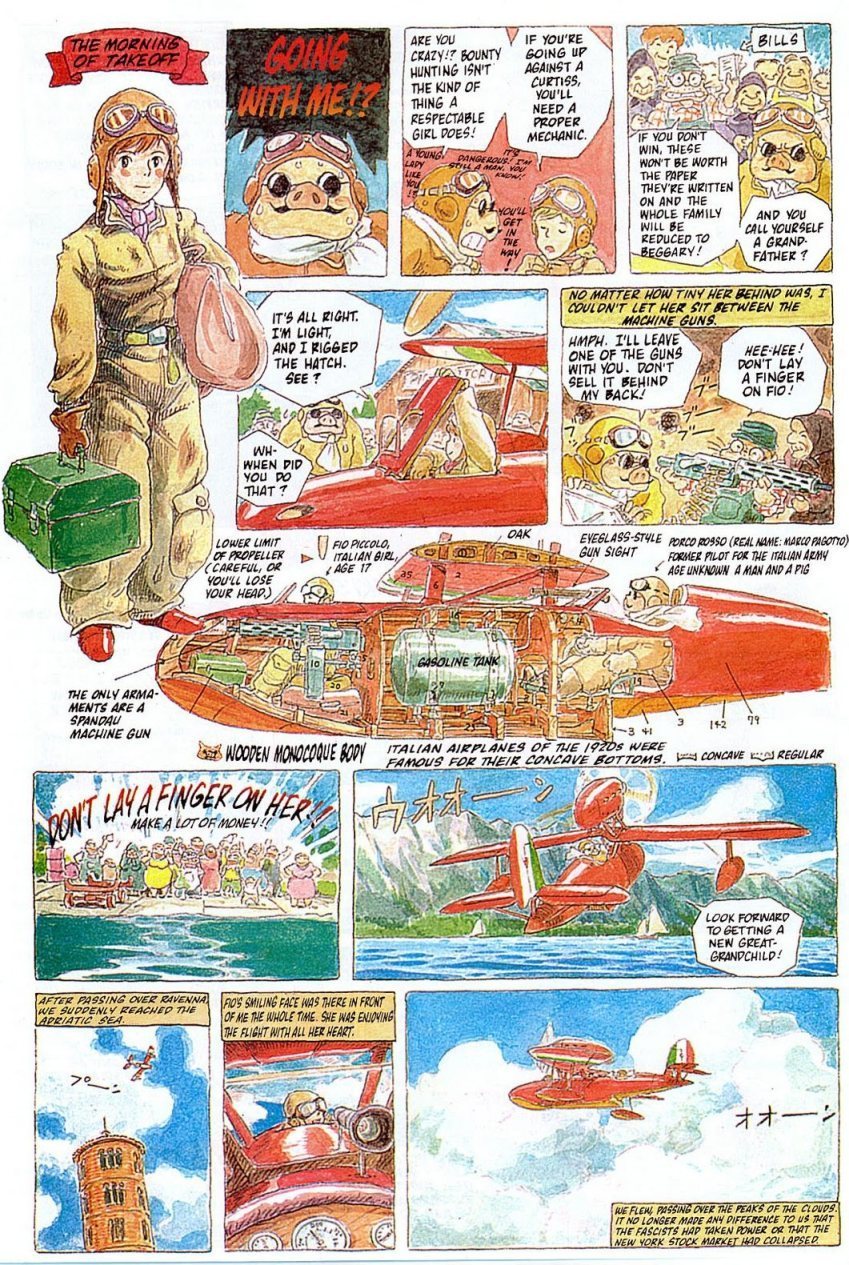

In 1989, Miyazaki published one of his new Notes, a short manga entitled Hikōtei Jidai (The Age of the Flying Boat) in Model Graphix, a magazine for aeromodellers, which collaborated with the mangaka on a regular basis. It was a fast-paced story of adventures that consisted almost entirely of aerial combat involving seaplanes dating from the 1920s. Miyazaki portrayed his protagonist who fought air pirates as an anthropomorphic pig — similar images of humanlike piglets were characteristic of his Notes as an element of the author’s peculiar irony.

The Age of the Flying Boat may have stayed one of Miyazaki’s many lesser known graphic stories had it not been for a happy coincidence. Shortly after the comic book was released, its creator had an idea to make a short, 30- to 40-minute-long, animated film at Studio Ghibli, to be aired aboard Japan Airlines planes. That commission stood behind the choice of aviation as the subject-matter and implied something light and entertaining, helping to pass the time on a flight. Miyazaki described it, “a movie which tired businessmen on international flights can enjoy even with their minds dulled due to lack of oxygen.”

However, the ambitious executives at Studio Ghibli weren’t satisfied. Although Miyazaki founded the project on The Age of the Flying Boat, short and comical, he increased its duration to a full feature and made the story incomparably more serious, complex and dramatic compared with the source. They say one of the reasons for that transformation is the fact that some of the events depicted in the film take place partly in the former Yugoslavia, where war broke out at the time of production. Those sad events arguably influenced Miyazaki, and it is partly under their impact that he added to his new work a strong anti-war message.

Studio Ghibli ultimately came up with a 90-minute animated feature known worldwide as Porco Rosso (Red Pig in Italian). Kurenai no Buta (Scarlet Pig) was the name used for Japanese distribution. As always, Miyazaki acted as director and scriptwriter, while co-founder of Studio Ghibli Toshio Suzukithe was invariably designated as producer. The film made its debut in Japan in July 1992. Over many years to follow, Porco Rosso survived the test of time and undoubtedly became a true Studio Ghibli gem. Its average MyAnimeList score is 8.03, IMDb user rating is 7.8, it has 94% positive critic reviews on Rotten Tomatoes and the overall 87% positive audience rating.

The role of this picture in Miyazaki’s creative legacy is notably controversial. Porco Rosso turned out to be in some sense a unique film and for a long time remained unmatched in its author’s creative heritage in terms of its plot, ambience and theme. Suffice it to say that for a long time it was Miyazaki only original film, in which the main protagonist is an adult man. The next “adult” film with an adult hero was released only twenty years later (The Wind Rises, 2013). There is even an opinion that Miyazaki was not very happy with Porco Rosso — in the 2013 documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness he makes a derogatory remark about “the adult film for children”. Anyway, we should not forget the creative perfectionism of the maestro, and no remark of his could ever nullify the audience’s love for his creation.

«A pig that doesn’t fly is just a pig»

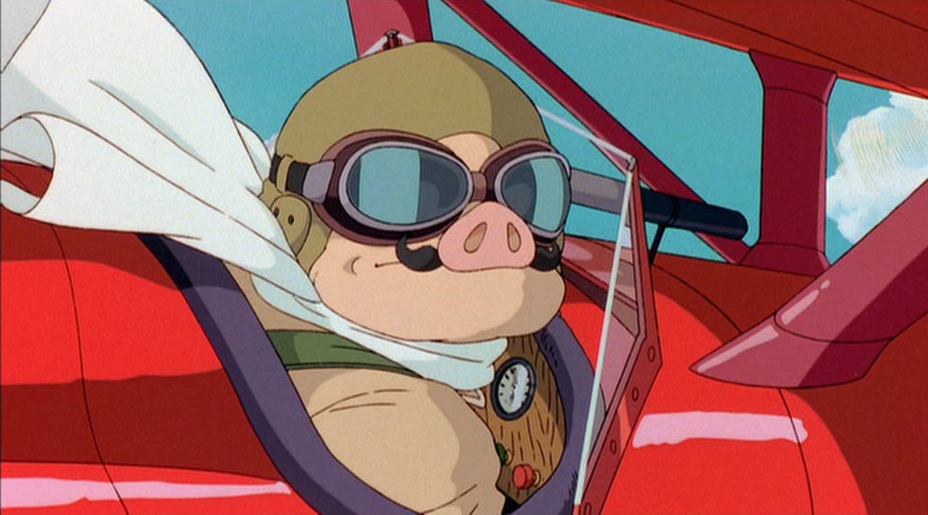

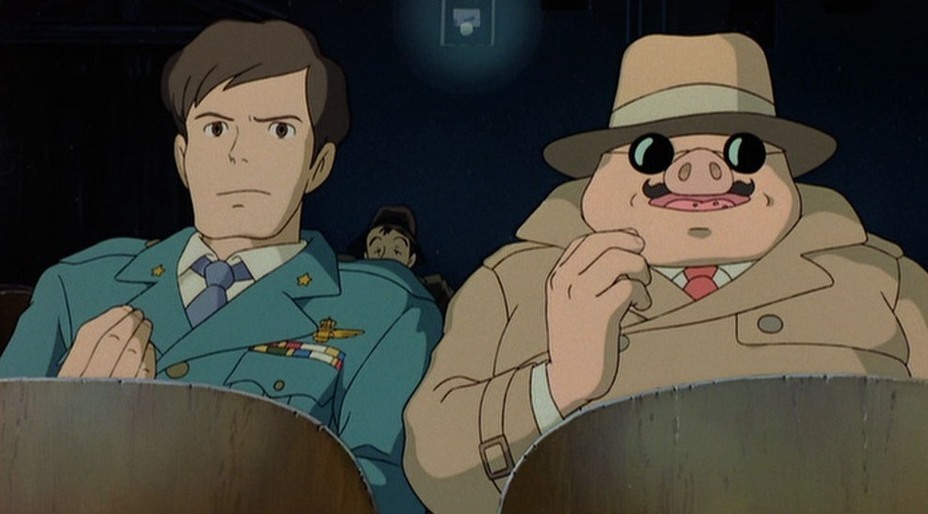

Porco Rosso can be identified as a sort of magical realism in a dieselpunk world. Its action takes place in the late 1920s in Italy and Croatia, on the shores of the Adriatic Sea. The protagonist of the film is a seaplane pilot, World War I veteran Marco Pagot. Marco lost his friends in the war, endured many ordeals, observed the victory of fascism in his homeland and was disillusioned in people so much that he turned into a humanoid pig (to be more precise, he is a man with a pig’s snout and ears). As mentioned above, anthropomorphic pigs are a popular comic image in Miyazaki’s drawings and manga (sometimes he even draws himself as such). In the film, this image has a much deeper and more tragic connotation, with Marco himself saying, “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist.”

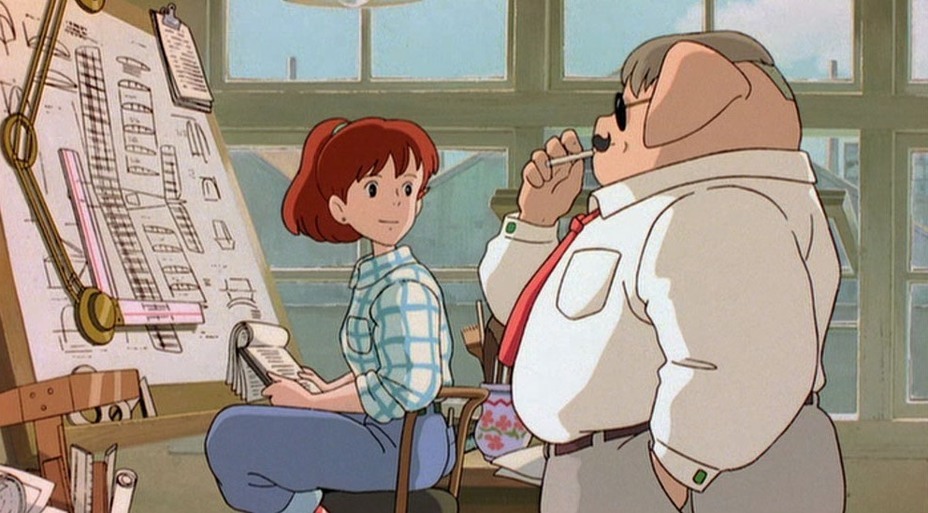

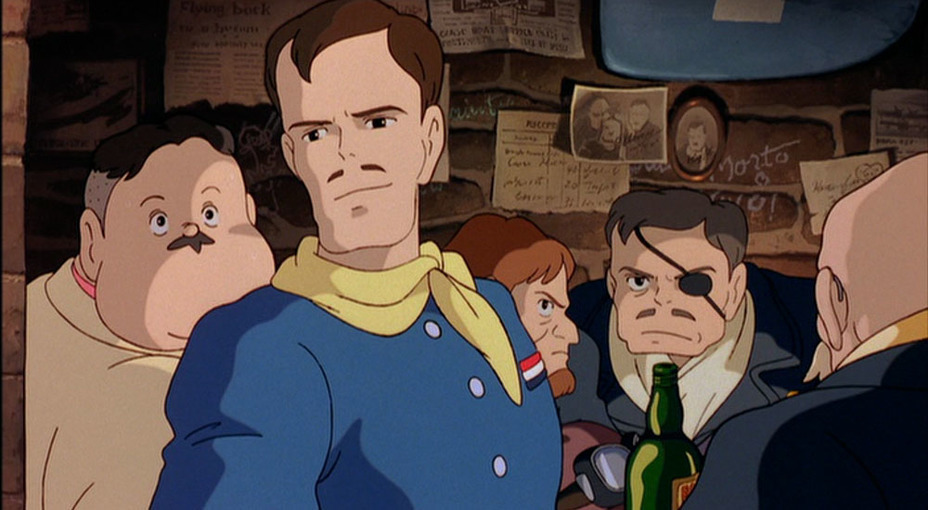

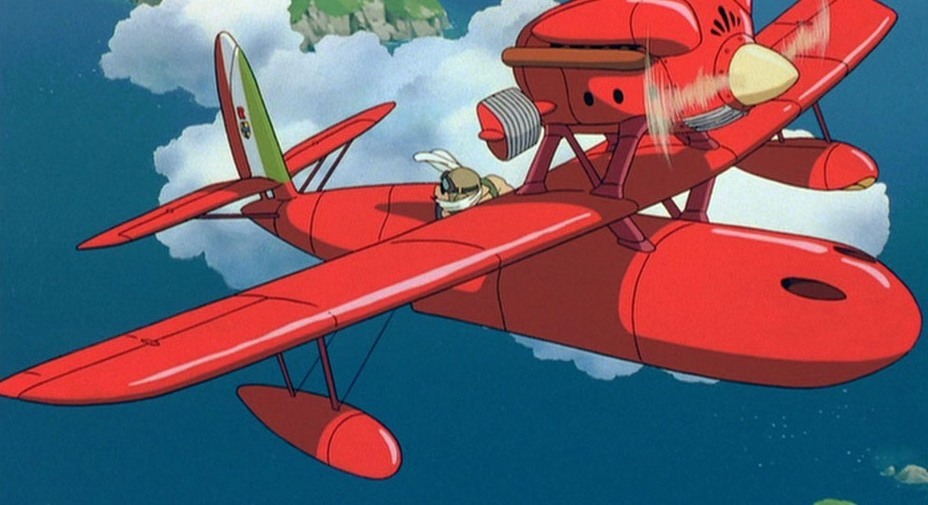

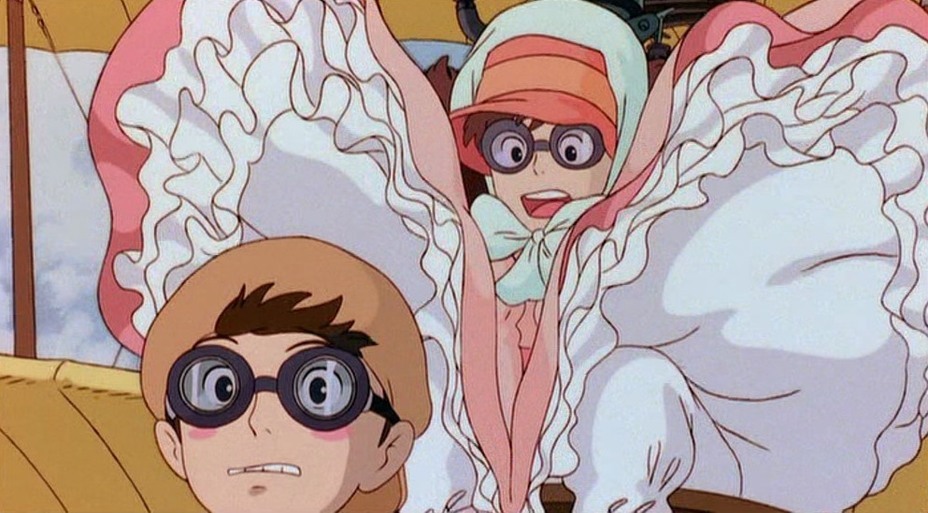

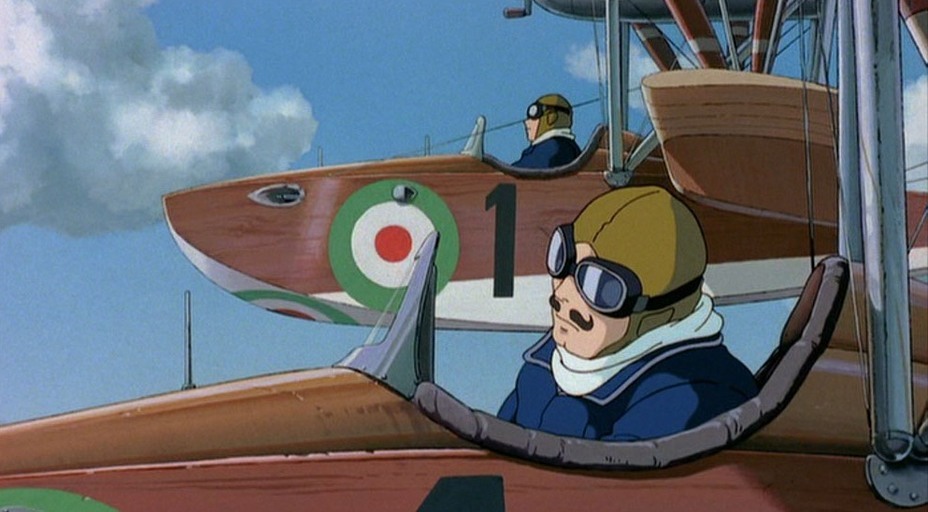

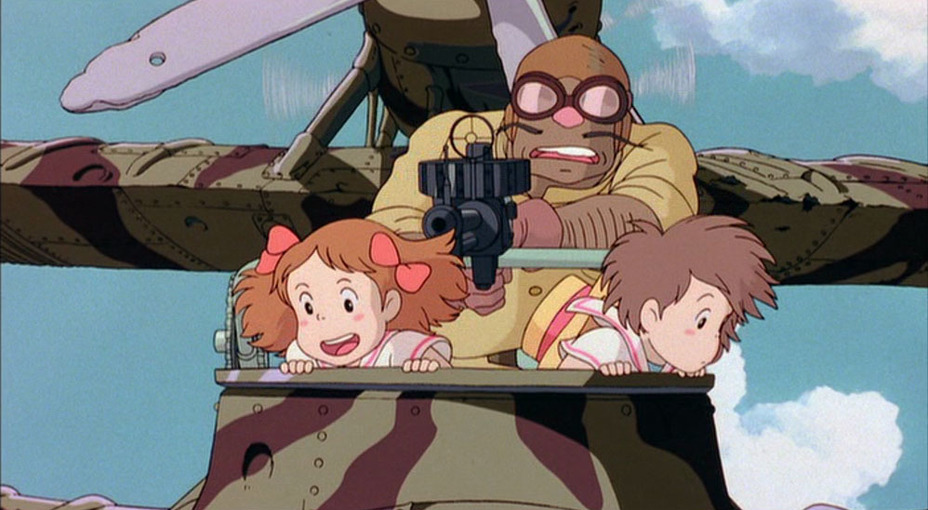

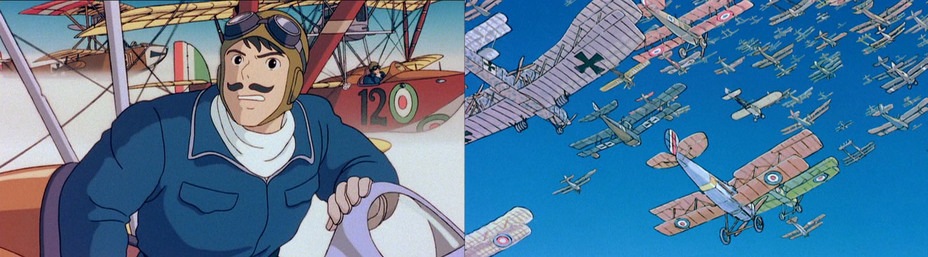

During the time captured in the movie, Marco is known as Porco Rosso (Red Pig, an obvious allusion to Red Baron). He pilots a powerful seaplane with a bright red hull (a fictional machine that resembles the Macchi M.33 and the SIAI S.21), lives on his own on a remote island near the Italian-Yugoslavian border and fights air pirates who raid the shores of the Adriatic Sea (20th century pirates use seaplanes instead of ships). Women are destined to play an important role in Porco Rosso’s life — his old unrequited love, the singer Gina, and his new friend, the young mechanic Fio. In addition, the cocky American aviator Curtis appears, thinking himself a worthy rival for incomparable Porco Rosso.

This brief description makes it clear that Porco Rosso can hardly be called a historical film in the strict sense. It is an amazing fantasy extravaganza, a savory combination of humor, fairytale, romance, adventure and love for technology with seriousness and drama. In this kaleidoscope, Miyazaki conveys the spirit of the time he describes with an amazing sensitivity, while demonstrating an incredible power of observation and tactfulness. His characters are members of the “lost generation” whose destinies were trampled down one way or another by World War I. Their lives are vivid and eventful, even positive in their specific way, but it is only a break between wars and turmoil. One could say that Miyazaki depicts a nook in a fairytale perfect Europe of the 1920s, a virgin territory untouched by disasters, where mostly good kind-hearted people dwell, and where even villains turn out to be funny simpletons. But the storms of the 20th century are upon them, and the clouds are already gathering: fascism, the Great Depression, new wars…

Porco Rosso is inexorably associated with the history of the early 20th century, including military history, but this connection does not imply a straightforward demonstration of historical facts — Miyazaki processes the material in a much more subtle and, one might say, spiritual way. In fact, the entire picture is a kind of homage to the aviation of the early 20th century and its heroes — pilots, mechanics, designers. The lead character started to fly back when the first planes came into existence; his fate is intertwined with the fate of aviation. The film features an entire collection of early aircraft, but even some of the fictional machines (like Porco Rosso’s hydroplane) are based on real planes. Despite his comical appearance, Porco crystallizes the characteristic image of a brave pilot of his time. He relishes the glory and proudly declares: “A pig that doesn’t fly is just a pig”

Marco Pagot’s frontline trials are shown briefly yet vividly. His war experiences are symbolized by the poignant memorable scene that Miyazaki borrows from Roald Dahl’s story “They Shall Never Grow Old”:

“Far ahead and above I saw a long thin line of aircraft flying across the sky. They were moving forward in a single black line, all at the same speed, all in the same direction, all close up, following one behind the other, and the line stretched across the sky as far as the eye could see. It was the way they moved ahead, the urgent way in which they pressed forward like ships sailing before a great wind, it was from this that I knew everything. I do not know why or how I knew it, but I knew as I looked at them that these were the pilots and air crews who had been killed in battle, who now, in their own aircraft were making their last flight, their last journey.”

The idea of a romantic, idealized brotherhood of aviators permeates the film. In one episode, Fio pacifies air pirates by telling them that she considers airmen to be honest and noble people. Fundamentally, there are no negative characters in the story at all — or rather, it is implied that they are behind-the-scene fascists, politicians, and militarists. The happy, almost carefree world, in which the characters of Porco Rosso live, is regularly invaded by harbingers of alarming times — news of the economic crisis, a military parade, a meeting with a friend who has joined the fascist air force. But the viewer wants to believe that friendship, love and mutual assistance will be stronger than the harsh reality, and the finale implies a relatively happy outcome for the protagonists.

The author contrived to keep a masterful balance between the various components of his film. It is a stunningly beautiful dieselpunk tale for adults, a romantic hymn celebrating the era of early aviation and, finally, a subtle and touching story about good people in difficult times. Surprisingly, Miyazaki created an anti-war and anti-fascist film that has no depiction of the horrors of war and miseries brought about by fascism. Porco Rosso is ultimately a bright, light and kind story in which, as befits a true fairytale, the good triumphs. Moreover, it is one of the most “adult” films by Studio Ghibli, with its plot and atmosphere hardly accessible to a child. In some ways, it is also a very personal work by Miyazaki, who (no matter what he said later) filled Porco Rosso with something exciting, close and dear to him personally.

There were reports in 2011 that Miyazaki allegedly wanted to make a sequel to Porco Rosso, and a possible storyline was revealed — Marco Pagot is fighting in the Spanish Civil War. There has been no news about Porco Rosso 2 so far, though, and Miyazaki has not uttered a word about it. Journalists must have misinterpreted facts, and nothing must have been originally said about the possibility of such a project (sequels are not Miyazaki’s cup of tea anyway).

And yet, the maestro returned to the agonizing theme of peace on the eve of the Second World War — albeit in a completely different story. The Wind Rises, produced in 2013, also focused on the aviation of the 1920s-1930s, but it turned out quite different, a lot gloomier and more tragic, almost devoid of any fairytale atmosphere. Nevertheless, for connoisseurs of Miyazaki’s work, it is uneasy to shake off the feeling that The Wind Rises is a kind of spiritual successor to Porco Rosso. For all their dissimilarities, it is also an ode to old aviation and its heroes, a reflection on love, war and history. The fact that Miyazaki decided to speak out on these issues again at the end of his career, tells volumes about how important they are to him.

Sources:

- animenewsnetwork.com;

- ghiblicon.blogspot.com.by;

- imdb.com;

- myanimelist.net;

- nausicaa.net/wiki/Main_Page;

- model.otaku.ru/porco/planes.htm.