In ancient Rome, war was viewed as a purely men’s thing and thereby inevitably envisaged sexual abstinence. Women were banned from camps — those who sneaked in were severely punished. As long as Romans fought close to their homes, or soldiers were allowed to stay with their families during winter months, this caused no serious trouble. But as campaigns grew longer and were waged farther from homeland, the prohibition of sexual contacts with women became increasingly difficult to enforce. Naturally, the military found a way out.

Soldier’s children

The kernel of the predicament faced by soldiers is well illustrated by a story told by Titus Livius. In 171 B.C., “another embassy, from a new race of men,” came to the Roman Senate all the way from Spain:

“(…) they, representing that they were the offspring of Roman soldiers and Spanish women, to whom the Romans had not been united in wedlock, and that their number amounted to more than four thousand, petitioned for a grant of some town to be given them in which they might reside. The senate decreed, that “they should put their names on a list before Lucius Canuleius; and that, if he should judge any of them deserving of freedom, it was their pleasure that they should be settled as a colony at Carteia, on the Ocean. That such of the present inhabitants of Carteia as wished to remain there, should have the privilege of being considered as colonists, and should have lands assigned them. That this should be deemed a Latin settlement, and be called a colony of freedmen.”

In the period between 205 B.C. and 175 B.C., some 70,000 Romans and 80,000 Italic allies visited Spain one way or another. In terms of Roman law, illegitimate children were unable to inherit their father’s civil status and therefore were not considered Romans. What made the situation especially dramatic was that Spaniards seemed to regard those descendants of mixed marriages as Romans and therefore also denied them the right to inherit citizenship and property in their mothers’ households. In other words, they became aliens in both their parents’ communities. Faced with the need to pass judgment on this confusing case, the senate found a simple yet effective solution by granting applicants the rights of Latin citizenship and moving them into a colony.

The name of the settlement in Cartaea, Colonia Libertinorum, or the colony of freedmen, brings up the issue of the status of Spanish women and their children of mixed marriages. The dominant idea is that those were slave women acquired by soldiers during their service in provinces. Accordingly, their children became freedmen. This, however, makes the legal incident described by Livius very unlikely. According to another hypothesis, soldiers would marry freeborn women and contracted marriages under local laws, which was not considered wedlock in Roman law. Unencumbered by any obligation, soldiers simply left their wives and children in the province as soon as they were discharged. In order to endow them with civil rights here, Lucius Canuleius arranged for a fictitious sale into slavery of 4,000 people with subsequent manumission. This is how the colony of Carteia received its name.

Soldiers and women from the provinces

The propensity of Roman soldiers to settle down with families in the provinces, where they were on garrison duty for a great while, was mentioned, among others, by Julius Caesar. During his visit to Alexandria in 47 B.C. he personally encountered the danger implied by this practice. It turned out that the Roman units that had been left here seven years before by the governor of Roman Syria, Aulus Gabinius, the so-called Gabinians, were completely corrupted and sunk into the mire of local strife. The notorious Roman discipline went up in smoke. Most of the soldiers had wives who had given birth to a horde of children. According to Caesar,

“they had all long settled in Alexandria. Here they assumed a kind of old military Alexandrian tradition to demand the heads of the kings’ friends, to plunder the property of the rich, to besiege the royal palace for a rise in wages, to expel kings from the kingdom and to summon others in their stead.”

Attempts to remove the Gabinians from the country in 50 B.C. and 49 B.C. failed. In the course of the conflict between Caesar and the people of Alexandria, which provoked a real war, the Gabinians sided with the Alexandrians and laid a three month siege to the royal palace, in which their countrymen had taken refuge. The ultimate victory over them was a hard one.

In order to separate Romans from provincials and prevent incidents of this sort in the future, Augustus adopted a series of laws to forbid Roman soldiers to contract official marriage during their active military service. Soldiers were not allowed to acquire property in the provinces where they were deployed, or dwell outside of their camps. The initiator of that legislation believed the arrangements would help boost his soldiers’ morale and maintain their discipline. As it frequently happens, the reality proved to be completely different.

Soldier marriages

The statistics of records and epitaphs of soldiers dating from the Imperial times indicates that they often had long-standing companions who gave birth to their children. It is believed that between the 1st and 3rd centuries about 1% of the soldiers from Mainz, 3% of those deployed at the garrison of Rome, and 5.2% of the soldiers from Carnuntum in Pannonia actually had families. Figures seem to be even higher in relatively peaceful provinces. For instance, out of the 354 military epitaphs of soldiers of the Third Augustan Legion stationed in Numidia, 206 (or 58%) mentioned spouses and children as the heirs to the deceased soldiers. In legal terms, those soldiers’ “wives” were mere concubines, and children they had with them were illegitimate. Upon their retirement, however, soldiers were entitled to legalize their relationships, at which point the state would recognize their children. Up to a certain moment the authorities had turned a blind eye to the very fact of cohabitation, while only insisting that those relationships could not be legally recognized throughout the duration of soldiers’ active service. It is believed that the final ban on soldier marriages was lifted by Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211).

The names of these soldiers’ “wives” suggest that most of them were freedwomen (liberta), that is, former slaves whom the soldiers had brought with them from home, bought locally, or obtained as spoils of war and who had subsequently been freed. Importantly, the law guaranteed the patron his priority right to cohabit with his freedwoman as a concubine (concubina), while avoiding the charge of adultery. Moreover, a freedwoman-turned-concubine was able to use the name, but not the rights of married women (matronae nomen) in those relationships. Some — but not all — Roman jurists allowed soldiers to take concubines from among freeborn women of mean birth, including former actresses or prostitutes. Self-sale into slavery with subsequent manumission may as well have been a legal ploy to enable at least a soldier’s freedwomen — if not his wife — to claim inheritance in the event of his death. Since technically that sort of marriage was considered illegal, the right to inherit through a will was recognized only for citizens.

Prostitution

The market for prostitution offered many soldiers an alternative to long-term marriage-like relationships. The low cost of sexual services in the Roman Empire — 2 assēs on average, equivalent to the price of a 1-pound loaf of bread — along with the considerable excess of supply over demand made those relations more economical and simpler than buying a slave or keeping a permanent concubine. For soldiers to visit a brothel was neither legally nor morally reprehensible. On the other hand, the military, especially veterans with some savings accumulated during their service, but also young soldiers and heirs to parental property, became a very attractive target group for entrepreneurs in the sex market. Most soldiers seem to have had very little difficulty finding a female companion among brothel boarders who would savor the rigors of military service for any period.

Accounts of this aspect of military life by contemporaries are not many. One of the few surviving reports is the well-known anecdote of how the champion of olden discipline Scipio Aemilianus expelled nearly 2,000 prostitutes from a Roman camp near the walls of Numantia in 133 B.C. The Roman army of 80,000 soldiers defeated by the tribes of the Cimbri in the Battle of Arausio in 105 B.C. is known to have had at least 40,000 auxiliaries and camp followers, traders and women. The Roman army of Quinctilius Varus, which was annihilated by the Cherusci in 9 A.D. in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, was accompanied by a crowd of non-combatants and women. These findings have recently been confirmed in the course of an archaeological dig at Kalkriese, where numerous bones of women and children were found along with the remains of men aged 25-45. A conservative source argued that this circumstance had the most negative effect on the battle training of soldiers and was one of the reasons for the defeat.

The Roman law defined a prostitute as a woman who made money by openly selling her body. Although prostitution was a legal profession for both sexes in the Roman Empire, it was considered a reprehensible trade in terms of public morality, which entailed a lowering of the social status (infamia) as well as deprivation of rights. For this reason, people refrained from mentioning it in epitaphs and personal records. We can assume that the majority of prostitutes were women from the lower social classes who were forced to sell themselves due to their poverty and lack of any other sources of income. Freedwomen and slaves who were leased out by their masters were forced into prostitution. The latter group included women kidnapped by brigands or taken from prisoners. According to Paulus Orosius, after defeating the Teutons, Tigurians and Ambrones in the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 B.C., the soldiers of Gaius Marius surrounded a large number of women in the camp. They responded to demands to surrender by begging guarantees that their chastity be preserved. When they failed to obtain their request, they committed mass suicide.

Brothels

Since women were banned from military camps, entertainments were concentrated in the trade and crafts quarters adjoining its walls — the so called canabae. They were homes to veterans or crippled soldiers who had no place to go after their service, gunsmiths, carpenters and other craftsmen who worked for the army, numerous merchants, entrepreneurs, pimps and criminals. Most of the buildings in canabae — workshops, warehouses, barns, temples, baths, etc. — served the needs of the soldiers. Over time, some canabae would grow so big that they were larger than the camp itself. Self-government bodies were established to organize social life there. Most of those settlements were eventually granted urban rights. In order to engage in their activities unhindered, the inhabitants of a canaba were supposed to obtain a special license from the magistrate of the settlement, and pay a respective tax, which was collected by soldiers.

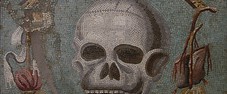

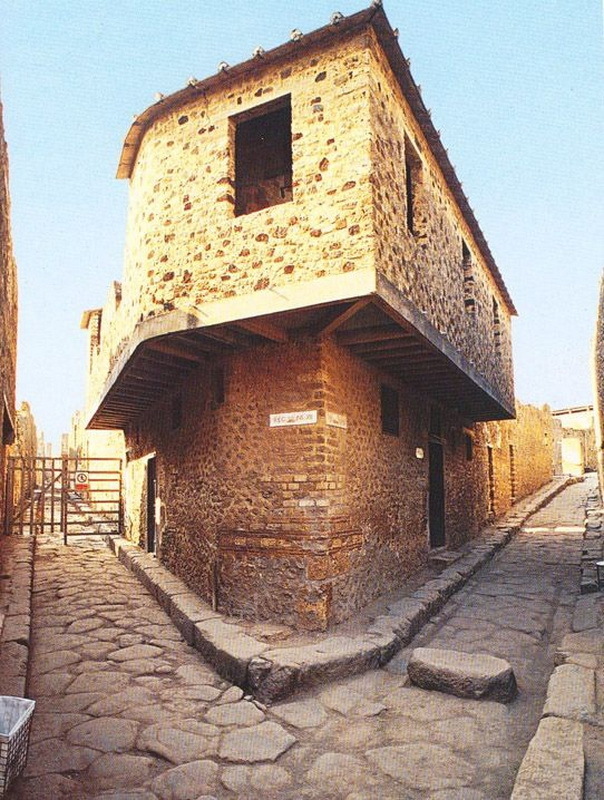

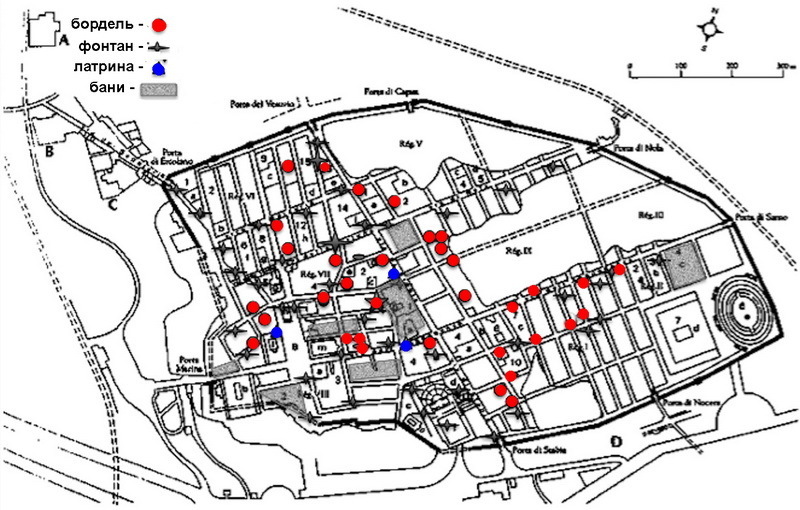

Lupanares (lupanarii) were special places for prostitution. We can get an idea of what those establishments looked like from descriptions in literary sources or from the excavated Lupanar of Pompeii. In Satyricon, the entrance to the brothel was separated from the street only by a curtain, behind which prostitutes walked around in light transparent garments or fully naked. The Lupanar in Pompeii, on the other hand, was a hallway with doors leading to two rows of rooms that were used for sessions with customers. There was no reception hall there to use for feasts and revels. The rooms separated from the hallway by curtains were small, obscure, and dirty, and seemed to be fit exclusively for the carnal business.

In addition to brothels, inns, taverns, public houses, guesthouses and baths were places traditionally associated with sexual pleasures. Those shady establishments could be found in any corner of the town. There were also prostitutes who received clients at home.

The house in block G5, excavated in the “civilian” part of Dura-Europos, a city on the right bank of the Euphrates river, was identified as a brothel. The purpose of the house was indicated by painted dipinto inscriptions on the walls, which mostly date to the last years of the Roman occupation. The main content of the inscriptions are lists of female names. Some of them are clearly associated with women engaged in the oldest profession. Some of the male names belonged to soldiers, one of whom was designated as optio. The position of stathmouhos, probably a quartermaster, was also mentioned in the inscriptions. The publishers of the documents assume that the building itself belonged to the army, and the brothel was organized there with the permission of the commander, who was concerned with his soldiers’ leisure. This hypothesis is supported by several references to a trip to or from Zeugma, the headquarters of the IV Scythian Legion, located upstream on the Euphrates.

Traders of human commodity

Women and men were supplied to army brothels by pimps, who would often move from one camp to another along the border. Flavius Philostratus, the biographer of the philosopher and wonderworker Apollonius of Tyana, shares the story of an amusing misunderstanding that happened to his protagonist in Zeugma:

“When they were passing into Mesopotamia, the publican at the bridge carried them to the toll-books, and asked what they brought with them. To whom Apollonius said, ‘I bring with me Prudence, Temperance, Justice, Continence, Fortitude, Patience,’ which he called by feminine names. The tax-gatherer, who thought of nothing but his fees, said ‘the names of the maids must be written in the toll-book’, to which Apollonius returned ‘Impossible, for they are not maids—they are mistresses, who travel with me.’”

Apparently, the publican mistook Apollonius for a human trafficker.

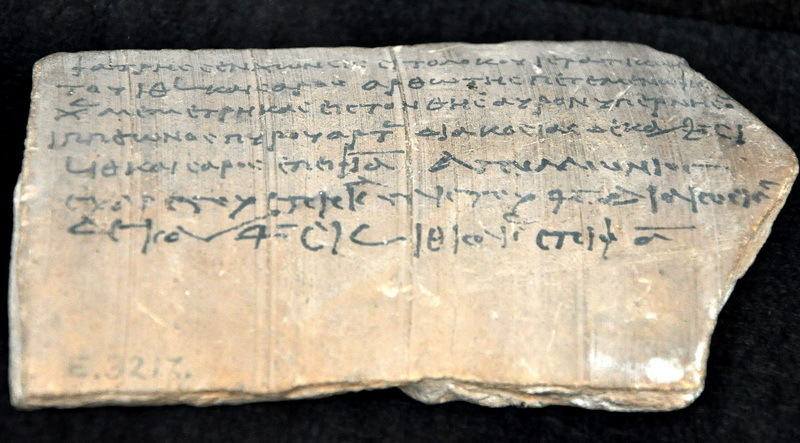

Not long ago, documents dating from the era of Trajan (98-117) were discovered in Egyptian Faiyum (the Greeks called it Crocodile City) with correspondence between the owner of this kind of business and his local agents supplying women to the Roman forts (praesidia) deep in the Eastern Desert between the Nile and the Red Sea. Those forts included garrisons of small units of soldiers who served on a rotation basis, leaving after each tour of duty. The contents of the documents shed light on how this business was organized and operated. Here is an example of such a letter on an ostracon, a large shard of pottery, on which daily correspondence was often conducted in Roman Egypt:

“N greets Ptolemus. I sent Procla to the praesidium of Maximianon for 60 drachmas and a quintana. Please send her onward with the donkey driver, who gives you this ostracon. I received a deposit of 12 drachmas, of which I paid 8 drachmas. Get (…) drachmas from the donkey driver. Give her a cloak. I will give her a tunic. Do nothing else.”

The name of the sender is not preserved. Ptolemus was his agent in Faiyum, whose duties included contacting soldiers and negotiating rates. As his boss’s letter implies, Ptolemus was supposed to take care of the delivery of women to their final destination, in this case the praesidium of Maximianon. As a rule, a contract was made for one month, and its normal amount was 60 drachmas less the quintana tax and 72 drachmas inclusive of the tax. At the end of this period, a woman would be sent to a neighboring fort, and a new one would arrive in her stead. Both the work and the pattern of movement along the chain of forts were referred to as kykleutikon — a cycle or circle.

Taxes

Prostitution was taxed by the Emperor Caligula (37-41), who set the amount of payment as the amount of one contact. Apparently, the tax was levied once a month, not per day of work as previously thought. Soldiers were responsible for collecting the tax and were known to commit frequent violations. For example, scholars discovered the remains of correspondence between the governor of Lower Moesia and citizens of Chersonesus, who lodged a complaint about extortion during the collection of the prostitution tax. Tax collectors probably had no difficulty in obtaining the required amount from brothel keepers or major suppliers, but it is not quite clear what sort of control could be maintained over women who received clients in their homes or sold their bodies while having some other occupation. Perhaps some form of licensing was in place, when municipal authorities issued a work permit to an applicant. One example is the fragment of a papyrus found in Upper Egypt:

“Pelai and Socrates, tax collectors, send their greetings to Tinabdella. We hereby grant you permission to have sex with anyone in this place on the day below. On the 3rd day of the month of Paopi, the 19th year. [signed] Socrates, son of Simon.”

In addition to the usual tax, the keepers of army brothels also paid a special quintana tax, which was referred to above. That tax was imposed on private contractors who had dealings with the army, and its amount was fixed. In the case of the documents from Faiyum discussed above the quintana amounted to 12 drachmas per month. As against other known prostitution tax rates from Egypt, which rarely exceeded 4 drachmas a year, the amount of the quintana looks impressive and probably attests to the lucrative nature of the business.

Sources:

- Campbell, B. The Marriage of Soldiers under the Empire / B. Campbell // Journal of Roman Studies. — 1978. — Vol. 68. — P. 153–166;

- Phang, S.E. The Marriage of Roman Soldiers (13 B.C. — A.D. 235): Law and Family in the Imperial Army / S. E. Phang. — Leiden: Brill, 2001;

- Pollard, N. Soldiers, cities and civilians in Roman Syria / N. Pollard. — Michigan, 2000;

- Speidel, M.A. Les femmes et la bureaucratie. Quelques réflexions sur l’interdiction du mariage dans l’armée romaine / M. A. Speidel // Cahiers du Centre G. Glotz. — 2014. — T. 24 — P. 205–215;

- Speidel, M.P. Lixia in the III Thracian Cohort in Syria / M.P. Speidel // Zeitschrift fur Papirologie und Epigraphic. — 1980. — Bd. 38. — S. 145–147;

- Cuvigny, H. Femmes tournantes: remarques sur la prostitution dans les garnisons romaines du désert de bérénice / H. Cuvigny // Zeitschrift fur Papirologie und Epigraphic. — 2010. — Bd. 172. — P. 159–166;

- Phang, S.E. The Marriage of Roman Soldiers (13 B.C. — A.D. 235): Law and Family in the Imperial Army / S. E. Phang. — Leiden: Brill, 2001;

- Pollard, N. Soldiers, cities and civilians in Roman Syria / N. Pollard. — Michigan, 2000.

- Speidel, M.A. Les femmes et la bureaucratie. Quelques réflexions sur l’interdiction du mariage dans l’armée romaine / M. A. Speidel // Cahiers du Centre G. Glotz. — 2014. — T. 24 — P. 205–215;

- Speidel, M.P. Lixia in the III Thracian Cohort in Syria / M.P. Speidel // Zeitschrift fur Papirologie und Epigraphic. — 1980. — Bd. 38. — S. 145–147;

- Cuvigny, H. Femmes tournantes: remarques sur la prostitution dans les garnisons romaines du désert de bérénice / H. Cuvigny // Zeitschrift fur Papirologie und Epigraphic. — 2010. — Bd. 172. — P. 159–166.