In 1910, several hundred inhabitants of the minute Micronesian island of Sokehs rebelled against the rule of the German Empire. Following the death of the head of the colonial administration, a German doctor had to lead the struggle against the local insurgents, while his army of Micronesians that remained loyal to the Kaiser was commanded by the island’s only policemen, a surveyor, and a Protestant pastor.

The Theater of Operations

There are a few archipelagos in the western Pacific that are traditionally grouped under the common name of Micronesia. This word, made of two ancient Greek roots μικρός (“small”) and nêsos (“island”), can be translated into English as a “Land of Small Islands”. This name is a perfect description of the very nature of this subregion of Oceania.

Micronesia consists of more than two thousand islands and islets with a combined area of hardly more than 2,700 square kilometers. This is roughly the same as the area of Moscow, at around 2,500 square kilometers after the radical change of 2012, when the territories of Novomoskovski and Troitski administrative districts were added to the capital city. However, the tiny islands are scattered over the vast oceanic area of 7.5 million square kilometers, which, for its part, is comparable to the area of the United States (without Alaska).

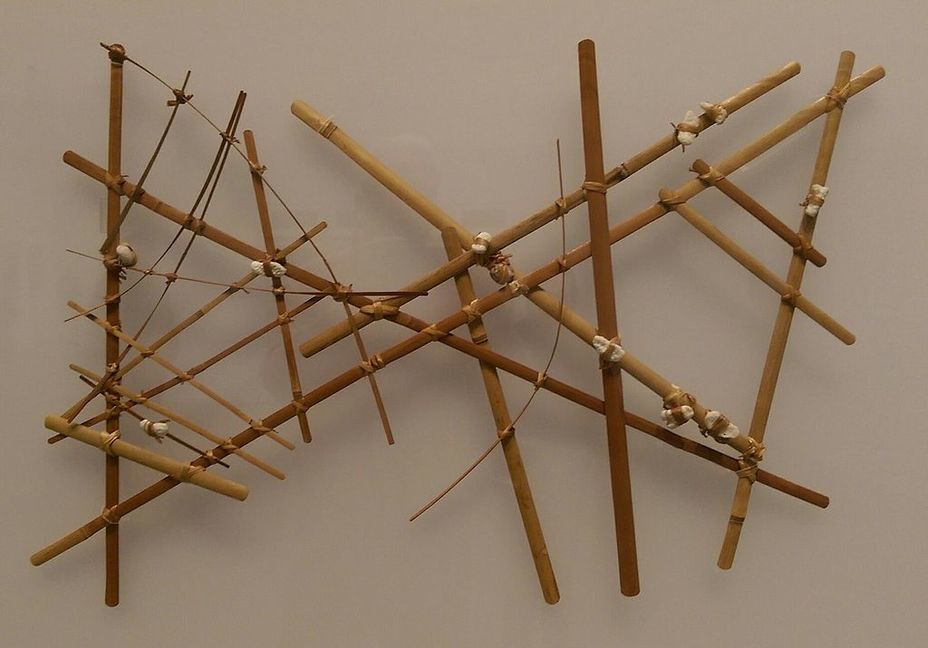

The earliest traces of human activity in Micronesia, discovered by archaeologists on the island of Saipan, date back to about 1500 B.C. The discovery and exploration of the islands, which are so distant from the Ancient World civilizations, only became possible after the ancestors of contemporary Micronesians came up with their own system of navigation, their traditional stick charts being its material embodiment.

Long before Europeans discovered Micronesia, its first state-like entities had been established. Since the start of the XII century, the large — by Micronesian standards — island of Pohnpei (344 square kilometers) of the Senyavin Islands that are part of the larger Caroline Islands group had been ruled by the mystic Saudeleur dynasty. Legend has it that the Saudeleurs were aliens to the island and were dissimilar from the natives of Pohnpei, which had been called Ponape up until 1984. The Saudeleurs had their capital at the city of Nan Madol, made of basalt stones, whose mysterious ruins are still there to observe and marvel at today.

In the 16th century, the Saudeleurs were overthrown by other aliens — probably from the Micronesian island of Kosrae (Kusaie) — who became rulers of Pohnpei and the surrounding islets. It was around the same time that Micronesia became part of the oecumene known to Europeans. In March 1521, the flotilla of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, on the first-ever circumnavigation campaign, reached the island of Guam of the Mariana Islands.

The first contact between Micronesians and Europeans was not particularly successful. The aborigines, obviously unaware of how the term “property” should be construed according to European law, stole everything they could find on Magellan’s ships. After a dinghy was stolen, the mariners could not stand it any longer, landed, burnt down the islanders’ village and returned the stolen goods. The first European name for the Mariana Islands was Islas de los Ladrones (Island of Thieves).

Eight years later, in 1529, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón, who unsuccessfully endeavored to return from the Moluccas to New Spain (Mexico) across the Pacific Ocean, discovered the island of Pohnpei. De Saavedra must have been fortunate and missed the native kleptomaniacs. The navigator chartered the islands Islas de las Hombres Pintados (Island of the Painted Ones) because the natives excelled at covering their bodies in tattoos. Incidentally, another Spaniard, Toribio Alonso de Salazar, may have been the true discoverer of the Caroline Islands (as we know the archipelago today), who three years previously had also discovered the neighboring Marshall Islands.

Spain did not hesitate and immediately declared the entire region of Micronesia and specifically Pohnpei their dominion. It was no more than a mere formality at first, though. There were neither spices nor other valuable goods here, and effective exploration of the islands on the other side of the world was out of the question. Spanish ships would visit local waters once every couple of years at best.

It was not until the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the Catholic Church finally got concerned about saving the souls of the Micronesians, who vegetated in paganism, that willy-nilly colonization of the Caroline Islands began. A royal decree issued in 1707 allowed sending missionaries to this part of the world, resulting in several expeditions, of which the first one was undertaken in 1710. However, after the potential congregation killed one of the preachers, Padre Cantus, attempts to Christianize the locals were suspended. It was much later, in the mid-19th century, that the Spanish kingdom unfroze its relationships with its “subjects” in the Caroline Islands.

In the 1880s, Spain finally signed treaties with several chiefs in the Caroline Islands, under which the latter recognized the Spanish king’s sovereignty over their lands. By that time, however, the archipelagos, which had practically been left to their own devices for centuries, had found themselves in the focus of the British and Germans, which provoked conflicts with the Spanish. To resolve the spat between Spain and Germany, even such a reputable arbitrator as Pope Leo XIII was engaged. In 1885, Spain had to cede a portion of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, to Germany.

Before the very end of the 19th century, the Spanish-American War broke out, which turned out so bad for Spain that it had to abandon — once and for all — all of its hope of returning to the elite club of great powers. The U.S. stripped it of some of the most important fragments of its once enormous colonial empire that had remained under the Spanish crown until then. Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines came under the control of the United States in one form or another. The Americans also occupied the largest Micronesian island of Guam, but they never descended to small change, such as the Mariana and Caroline Islands.

Under the Kaiser

It is here that our story starts.

Having curbed its great-power ambition, Spain decided it should not wait for its remaining overseas possessions to be taken by force. In 1899, it sold the Caroline and Mariana Islands to Germany for 25 million pesetas (17 million marks). These archipelagos became part of German New Guinea, a vast colonial possession that included, in addition to the new acquisitions, Kaiser-Wilhelmsland (northeast of New Guinea), the Bismarck Archipelago, the Northern Solomon Islands, the Marshall Islands, and Nauru.

The Germans embarked on colonization with their natural thoroughness. In the context of Pohnpei, they intended to build a network of roads to ensure a more effective control of the recalcitrant locals. To procure enough manpower for this ambitious project, labor conscription was imposed on the natives of the island.

Pohnpei had once been a single state under the Saudeleur dynasty. Later in its history the island went through a period of “feudal fragmentation”, when it was home to several “kingdoms”. Sokehs was one of those proto-state entities, a “kingdom” on the island having the same name, separated from the northwestern shore of Pohnpei by a narrow strait. The inhabitants of Sokehs were not the aborigines of Pohnpei, as they descended from those settlers who originally arrived from the Gilbert Islands (currently Kiribati), and were notable for their fierce need for independence.

As soon as Kolonia, the island’s administrative center, was connected to the remote southern “kingdom” of Kitti, the German administration made up its mind to build a road around Sokehs with its infamously freedom-loving inhabitants. Their reputation among the colonizers was well-deserved, for it was the natives of Sokehs that had once revolted against the Spanish rule on Pohnpei.

By introducing labor conscription, the Germans brought about a serious disruption to the entire system of relationships between the local peasants and the elites. Land had traditionally been viewed as the property of the local noblemen, who had granted it to their tribesmen in exchange for a large portion of the harvest. The Germans put in place a land reform, though, dividing the land among the local tillers and effectively replacing the tribute with forced labor. Instead of paying a tax, peasants were now supposed to spend 15 days a year on public works.

The two German overseers on the island, Otto Hollborn and Johann Häfner, as well as one of the local chiefs, Samuel, with a rank of Sou Madau (“master of the ocean”), were assigned to supervise the construction of the road around Sokehs. This time, the Germans made a huge personnel mistake. Hollborn let things slide, and it was his local mistress, a native of another island “kingdom”, that supervised the workers instead of him. The inhabitants of Sokehs found such a degrading attitude to be humiliating.

Even a more serious blunder was the assignment of Samuel as an overseer. The ambitious chief was extremely unhappy about his role as a collaborationist. In the end, he inspired his countrymen to fight the hateful colonizers. His chances of success weren’t slim at all: there were no German warships new Pohnpei at that time, and the handful of Germans on the island were unable to put up a fight. Moreover, they soon helped Samuel by offering him a suitable pretext for starting a rebellion.

On October 17, 1910, one of the laborers refused to work and was ordered flogged by Hollborn for his transgression. The German official would have thought twice, had he been aware of local customs. Human skin was a taboo for the islanders, and the one who injured a native would face his entire tribe seeking revenge. In addition, the punished laborer belonged to a family of chiefs. Sou Madau Samuel took advantage of the situation and organized a strike. In the morning of October 18, the two German supervisors saw that the situation had reached rock bottom and fled to the Capuchin mission compound on Sokehs Island.

Gustav Boeder, head of the colonial administration of Pohnpei, learned about the developments and rowed to the island with his assistant Rudolf Brauckmann. But instead of negotiating with Samuel, Boeder was shot in the head and killed. The rebels then used rifles and spears to kill Brauckmann, several Micronesian oarsmen, and the overseers Hollborn and Häfner, who had run out of the mission building towards the lifeboat hoping to escape.

The unwilling governor

After Boeder’s death, Max Girschner, the colony’s medical doctor and the new head of the German administration, had to lead the fight against the Micronesian insurgents. The first challenge the new “governor” of Pohnpei had to tackle was to organize the defense of the island’s capital of Kolonia. Girschner’s acts were quick and decisive, as befitted a soldier. Since the policeman Karl Kammerich was the only representative of the German “law enforcers” on the island, the doctor sought help from the chiefs of the other four “kingdoms” of Pohnpei. Three of them — Nett, Madolenihmw and U — immediately sent their troops to the aid of Kolonia, pending siege, and Kitti dispatched its warriors a little later. The “loyalist” units were 600 men strong.

The leader of the rebels, Samuel, had about two hundred fighters wielding a few Remington rifles and ammunition stolen from military depots during the Spanish rule. Pohnpei used to have substantial stocks of firearms, and the colonial administration prudently sought to remove them from the island. After a terrible hurricane that destroyed crops, the islanders were on the verge of starvation. The Germans took advantage of the situation and invited the Micronesians to exchange a rifle for 35 marks, or four sacks of rice, or 20 cans of food. The natives received 10 pfennigs for each cartridge they surrendered. The “arms for food” campaign proved quite successful — about 500 rifles and several thousand rounds were exchanged for food. However, some of the islanders, including those from Sokehs, retained their arsenals.

Doctor Girschner was the one responsible for the overall management of defenses of the capital city. His deputy was the surveyor named Dulk, whereas the third and fourth officers were the aforementioned policeman and the Protestant pastor Hagenschmidt. Led by that unique officer corps, the inhabitants of Kolonia and the warriors sent by the loyal chiefs built a rampart on the approaches to the town and turned the prison, along with the Catholic and Protestant churches, into their strongholds. At night the defenders of Kolonia illuminated the road leading into the capital with lanterns.

The confrontation on Pohnpei was quite sluggish all the way until late November 1910. Unable to enlist support of the remaining Micronesians, Samuel’s followers entrenched themselves on Sokehs with insufficient forces to oust the Germans and their allies from the bigger island. On the other hand, Girschner had no contact with the outside world, and the German Empire remained unaware of the uprising that shook its colonial domain for more than a month. The doctor and his “officers” did not dare invade Sokehs with the limited forces of the natives at their disposal.

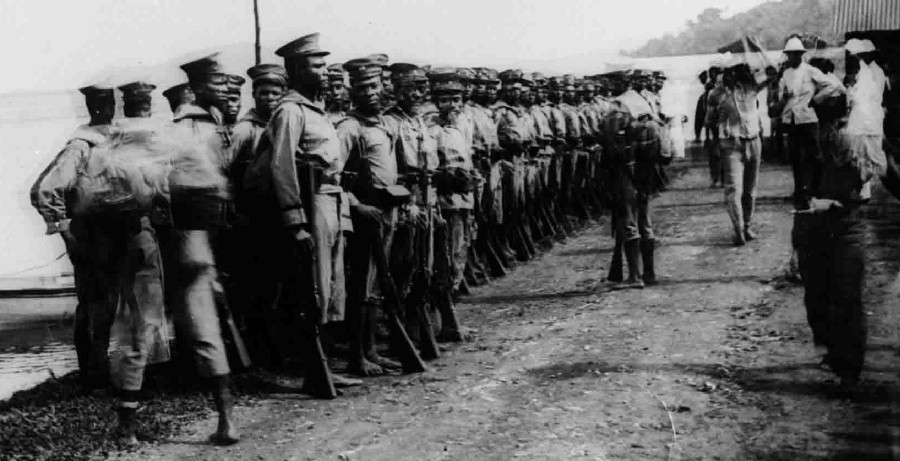

The stalemate was broken on November 26, when the mail steamer Germania appeared in the harbor of Kolonia. That ship delivered a message about the critical situation on Pohnpei to Governor of German New Guinea Albert Hahl at Rabaul. Hahl outfitted a rescue party consisting of the small cruiser SMS Cormoran and the survey ship Planet, with 163 newly hired Melanesian police recruits aboard.

In mid-December, the backup reached Pohnpei. The Melanesian policemen, led by the chief of police Kammerich, took over the defense of Kolonia, and the Germans’ Micronesian allies from the “kingdoms” of Kitti, Nett, Madolenihmw, and U went home. Kammerich, having a unit of Melanesian recruits, attempted to jump into action, but to no avail.

On January 10, 1911, two German light cruisers SMS Emden and SMS Nürnberg approached Ponape. On January 13, they opened fire on rebel positions on Sokehs. A combined detachment of armed sailors and Melanesian police landed on the island. The rebels of Sokehs were forced to turn to guerrilla warfare methods. Since their home island was too small for their activities, some of the rebels moved to the larger island of Pohnpei. Samuel’s supporters even managed to build a stone fortress in the “kingdom” of Nett, but as soon as it fell, they had to retreat to the caves of Impeip.

The suppression of the rebellion was taking too long. It was only possible to force the Sokehs guerrillas to surrender after the Germans began destroying food sources in the areas of combat — breadfruit trees, taro and yam fields. On February 13, Samuel was captured, and on February 22 or 23, 1911, his last starving supporters had to surrender.

The trial of the rebels was swift. On February 24, the 15 rebels sentenced to death, including Samuel, were shot by a firing squad. Moreover, at least six Sokehs insurgents were killed during the skirmishes. In addition to those killed during the first day of the uprising, the German side lost one noncommissioned officer and two sailors, alongside two Melanesian policemen. Another German naval officer, five sailors, and nine Melanesians were wounded.

The Aftermath

After the crushing defeat of the rebellion, the German colonial administration made a radical move to address the problem of the troubled island of Sokehs by relocating its 426 inhabitants to Babeldaob (currently the main island of the Republic of Palau). Their forced migration was short-lived, though. In 1914, German Micronesia was occupied by Japan, which had joined the Entente in World War I. Over one decade from 1917 to 1927, the Japanese resettled the original residents of Sokehs to their homeland.

In the wake of World War II, Micronesia, which became an arena for much more serious battles, changed hands once again. This time it came under the control of the United States. After the war, the Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana Islands (with the exception of Guam) became part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, under the authority of the U.S. Navy and later, of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

In the fall of 1986, parts of Micronesia became independent — the Republic of the Marshall Islands and (in the eastern Caroline Islands) the Federated States of Micronesia were established here. Later, in 1994, the Republic of Palau, located in the western Caroline Islands, also gained independence.

Pohnpei is currently the main island of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). It constitutes the core of the state with the same name, the largest of the four FSM states by the area and the second-largest one in terms of the population. It was on the same island, eight kilometers from its capital Kolonia, that the capital of FSM, Palikir, was built.

Sou Madau Samuel is celebrated as the national hero of the Federated States of Micronesia, and the communal grave of the 15 rebels shot by the Germans is venerated as a shrine.

Sources:

- José Saínz Ramírez: «Imperios coloniales», editorial Nacional, 1942, Madrid;

- Милослав Стингл: «По незнакомой Микронезии», Москва, изд-во «Наука», 1978;

- Peter Sack: The ‘Ponape Rebellion’ and the Phantomisation of History, Journal de la Société des océanistes, 1997, Volume 104, Numéro 1, pp. 23–38 persee.fr;

- Thomas Morlang: Die Polizeitruppe Deutsch-Neuguineas 1887–1914, traditionsverband.de;

- The Catholic Church In Palau, .