In the summer of 1944, the British capital city was showered with unprecedented lethal shells, as the Germans began bombing London with their latest cruise missiles. However, the Brits, warned by their intelligence, were ready for this and employed inter alia their air defense assets alongside fighter aviation. What were the tactics of the pilots who flew Mosquitoes and Tempests and were they truly successful?

Those weapons were known by different names: their brand name Fieseler Fi 103, the Luftwaffe designation FZG 76 (Flakzielgerat – “target for anti-aircraft gunners”), but the most commonly used name was the V-1 (Vergeltungswaffe – “vengeance weapon”), given by Goebbels’ department.

Their story began in October 1939, when the Argus company came up with an unmanned remote-controlled bomber based on its target drone. The piston-powered bomber eventually evolved into a cruise missile powered by a pulsating air-jet engine, and in February 1942, Fieseler joined the project. Flight tests of the unpowered version started in October of the same year, whereas in December, the first tests of the version equipped with the engine were conducted. In the summer of 1943, the buzz bomb was put into full production.

Around the same time British intelligence not only learned about the new weapon, but also managed to get hold of the wreckage of one of the missiles following its tests. In autumn, it linked the advent of the new weapon with the numerous launchers built in the Pas de Calais, Upper Normandy and the coastal portion of Picardy.

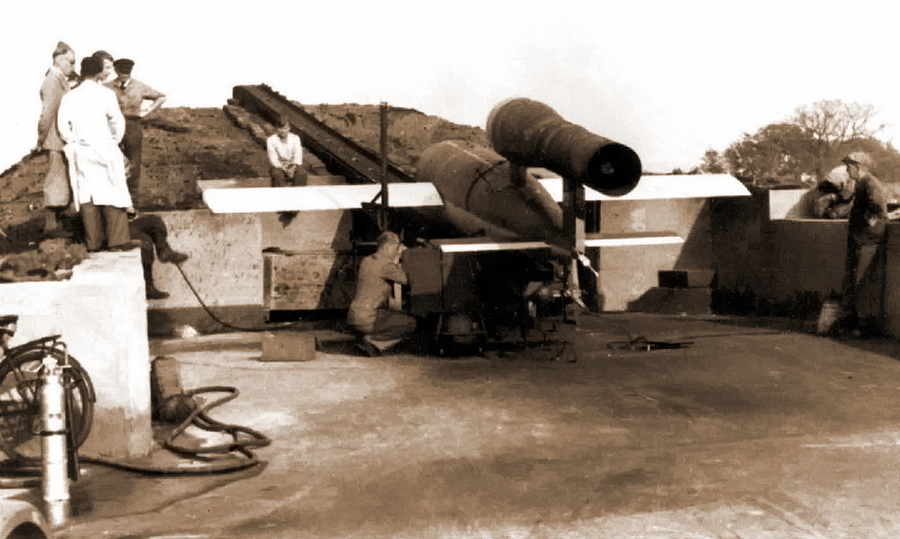

Acknowledging the threat, as early as December 1943, the Allies began to raid the launch sites. All in all, the Crossbow Anglo-American operations (against research and development of ballistic and cruise missiles, manufacturing and launch sites) spanning the period between August 1943 and March 1945, comprised almost 69,000 sorties, with over 122,000 tonnes of bombs dropped on enemy facilities. Operation Crossbow proved to be a serious impediment to the work of the 155th Anti-aircraft Artillery Regiment (code name of the unit responsible for ground launches of V-1), but never managed to stop it altogether, and the night of June 13, 1944 saw the first bombing of London with buzz bombs.

The first pancake was a blob, as Russians say — only nine missiles were launched during the debut salvo, none of which reached the shores of England. Another salvo followed in a few hours, but only four out of ten shells crossed the island’s coastline, and only one hit the British capital.

First hits

After the three-day recess, during which time heads-up about German jet “robot planes” (they were soon codenamed Divers) was given to all daytime and nighttime fighter squadrons across Britain, the Mosquito crews on patrol over the English Channel already knew what they might encounter and understood the importance of destroying new targets, when the Germans resumed launches on the night of June 16.

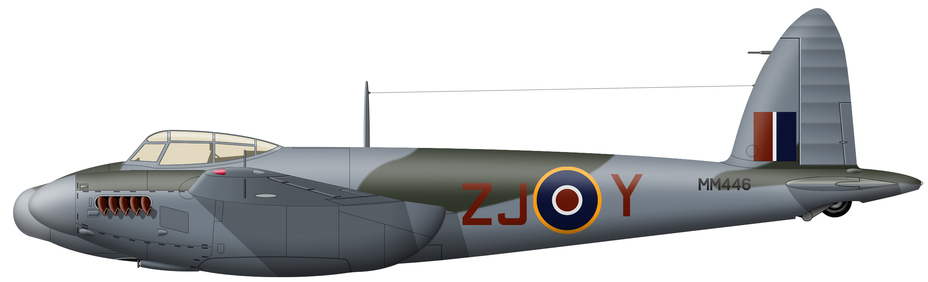

At 0:40, Flight Lieutenant John Musgrave (pilot) and Flight Sergeant F. W. Samwell (navigator) in a Mosquito FB Mk.VI of No. 605 Squadron, observed a fireball rapidly passing them at the same altitude several thousand feet away, some 20 miles off the Dunkirk traverse. Quickly turning around, the pilot rushed in pursuit. Three cannon bursts later, a huge explosion with a bright flash followed, and the wreckage of the “robot” fell into the water.

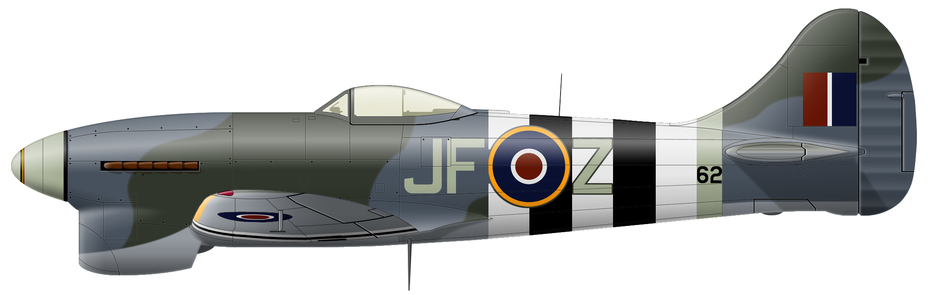

The first air victory over the V-1 was achieved, and the pilots were credited with a total of four downed bombs that night. In the morning daylight fighters went on patrol and at 7:50, Flight Sergeant Maurice J.A. Rose of No. 3 Squadron RAF piloting a Tempest Mk.V shot down another doodlebug, which marked the first of the 12 daylight victories won that day.

A total of 244 buzz bombs were fired at London from 55 launchers during the day, of them 144 reached the territory of England, including 73 that hit the British capital. Twenty-five flying bombs were shot down by anti-aircraft fire, seven by fighters (counting only those shot down over land).

That morning the War Cabinet called into play the developed plan of defense against cruise missiles, which had to be modified only slightly to make up for the dispatch of some anti-aircraft means to Normandy by increasing the number of fighters and balloons. In that scheme, interceptors were assigned two patrol areas: one over the English Channel from one coast to the other, and the other one between the anti-aircraft engagement zone along the coast and barrage balloons on the outskirts of London and some other cities. The first zone was predominantly a night one, whereas the second one was a day area.

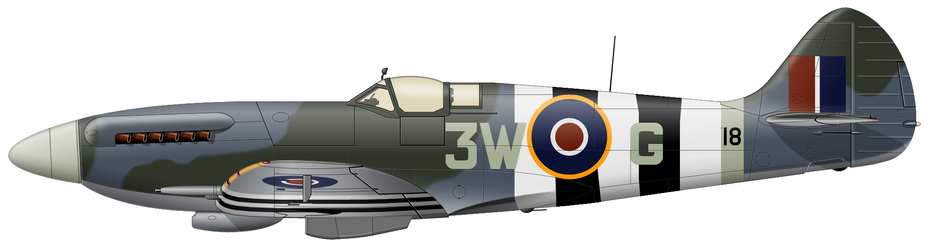

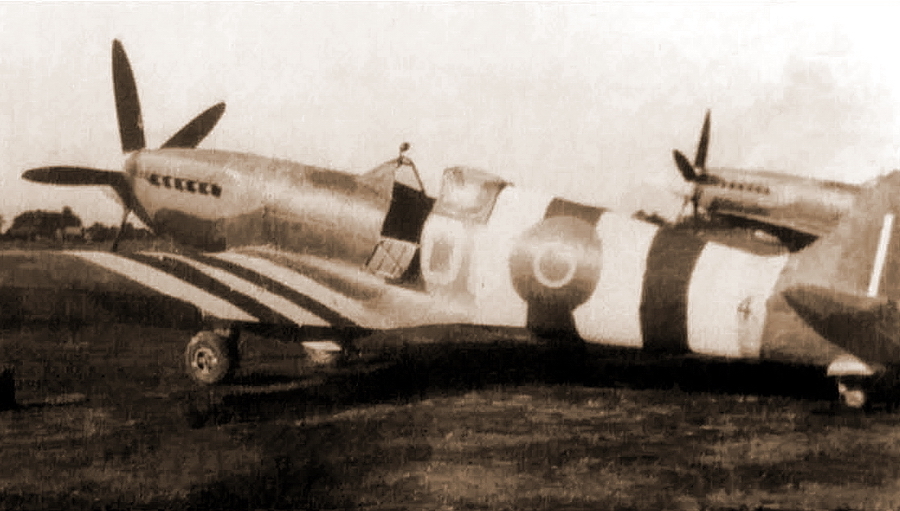

Even faster interceptors were called for to shoot down high-speed targets. The command focused on the latest Griffon-engined Spitfires and Tempests, initially assigning five squadrons to fight the V-1 — two flying the Tempest and the Spitfire Mk.XIV and one operating the Spitfire Mk.XII. However, the increased intensity of bombings with doodlebugs immediately required a build-up of the interceptor force. Within a week, the anti-Diver force gained three more squadrons, flying the Spitfire Mk.XIV, the older Mk.IX, and the Typhoon fighter-bombers. For the latter unit, hunting V-1 bombs was not a priority mission, and its pilots performed patrol work only when there were no reconnaissance or attack missions for them.

In July, the air defenses were further reinforced by six squadrons: four on the Mustang Mk.III, one on Tempests and one on the latest Meteor Mk. I jet fighters. By August, the total number of RAF squadrons assigned for daytime intercepts of buzz bombs had increased to 15 with some equipment changes: five flew Tempests, four Spitfires Mk.XIV and Mustangs each, and one flew jet fighters and Spitfires Mk.XII each.

Practicing tactics and new techniques

Interceptors’ typical tactic was to patrol along the anti-aircraft artillery engagement area and when the “bomb” came out of the zone, a nosedive followed with a simultaneous turn so as to fly horizontally directly behind the target at a distance of effective fire. The high flight speed of the V-1 left interceptors no more than two to three minutes for their attack. At the same time, long-range fire normally disabled the engine or damaged the control system, so the projectile simply fell down prematurely, often on populated areas on its route. So the idea was not just to shoot down a buzz bomb, but to make sure that it exploded in midair. In order to do that, it was necessary to get closer.

A pilot ran the risk of being hit by the blast and debris of a downed Diver. On June 19, a Spitfire Mk.IX of the Norwegian No. 332 Squadron RAF was lost for this reason, whose pilot, Sergeant Eivind Veiersted, escaped by parachute. It was not unusual for fighters to return to their bases with their hulls smoked or burnt.

There were a few collisions as well, with at least one being intentional: Captain Jean-Marie Maridor, a French pilot of No. 91 Squadron RAF, fired at a V-1 bomb over Kent on August 3 and successfully hit the target. But the warhead failed to detonate and the buzz bomb with its failed engine began to fall directly on a hospital, which was clearly visible from the air due to the large red cross on its premises. According to eyewitnesses, there was no time for a second pass: the Frenchman rammed the bomb and died in the explosion.

Interceptions over the English Channel looked somewhat easier because of the lower speed of the Divers, which still had most of their fuel on board, and the lack of the need to blow up the target in midair. Most of the attacks over the water were delivered during other missions, rather than anti-Diver patrols. Low-altitude Spitfire LF Mk.IX squadrons engaged in Operation Crossbow were shooting down V-1 bombs more frequently than other units, including American squadrons, which also contributed, though.

The Hispano 20 mm M1 automatic wing-mounted gun became the main weapon against the V-1, but a more exotic technique also gained some popularity. It was originally tried on June 23 by Captain Maridor’s mate, flying officer Kenneth R. Collier of No. 91 Squadron, who piloted a Spitfire Mk.XIV. He began a routine attack and fired from a normal range, but in four passes he spent all of his ammo without having a hit.

According to the pilot’s testimonial, he decided to follow the classic “do or die” recipe, caught up with the bomb and brought the wingtip of his fighter under the doodlebug’s wing. Then Collier sharply pulled the control stick toward him, hoping to flip the flying bomb on its back. He failed the first time, but his second attempt was a success, as the primitive autopilot of the buzz bomb did not cope with the large roll and it lost control.

Unfortunately, no exact statistics are available for the number of buzz bombs toppled by fighters, but we know the name of the record holder in a single flight — Flight Lieutenant Gordon L. Bonham of No. 501 Squadron, who piloted Tempests. On August 26 he used up all his ammo to shoot down the first V-1 and then toppled three more.

In the night skies

The shelling of London with flying bombs was a round-the-clock endeavor from the outset, so night fighters had an important role in protecting the British capital. Initially four squadrons of Mosquito fighter-bombers and night interceptors of various makes were assigned to fight the V-1. The group was soon reinforced by five more squadrons, as well as one special unit. That FIU (Fighter Interception Unit) practiced night fighter operations and also used Mosquito bombers, but in the summer of 1944, a Tempest flight was organized as its part, whose pilots operated around the clock. At the end of August, the flight was incorporated into No. 501 Squadron, which also inherited the night interception function.

Furthermore, pilots from other squadrons of Tempests and Spitfires occasionally flew at night, but they did not make a real difference. For a few days in mid-July and then for most of August, one American squadron of night fighters flying P-61 heavy twin-engine fighters was also part of the air defense system.

Night fighters patrolled the skies over the English Channel and preferred staying close to the French coast, whereas some crews “hovered” directly over the launcher areas to start pursuit immediately after launches, as the flare of the rocket engine was visible from afar in the darkness. As soon as a target was detected, a dive followed for a fighter to fly horizontally in close proximity to its target and deliver a short attack: most Mosquito versions lacked the speed for any extended pursuit. As in the daytime, it was not uncommon for aircraft to be damaged or lost by close V-1 blasts, but the twin-engine configuration gave them a better chance of reaching the shore.

All in all, the Germans fired 8,617 cruise missiles at England during the summer campaign of 1944. Of them 1,052 fell immediately after takeoff, 2,704 were lost over the English Channel, 3,855 were destroyed by the British air defense, and only about 2,300 fell in relative proximity to their assigned targets (counting those shot down that did not explode in the air).

Shelling peaked in July, and then the Allied offensive forced the Germans to begin evacuating. At 4:00 on September 1, the last ground launch of the V-1 from occupied France was carried out, but it did not eliminate the threat completely, because there were still air-launched cruise missiles.

Air launch

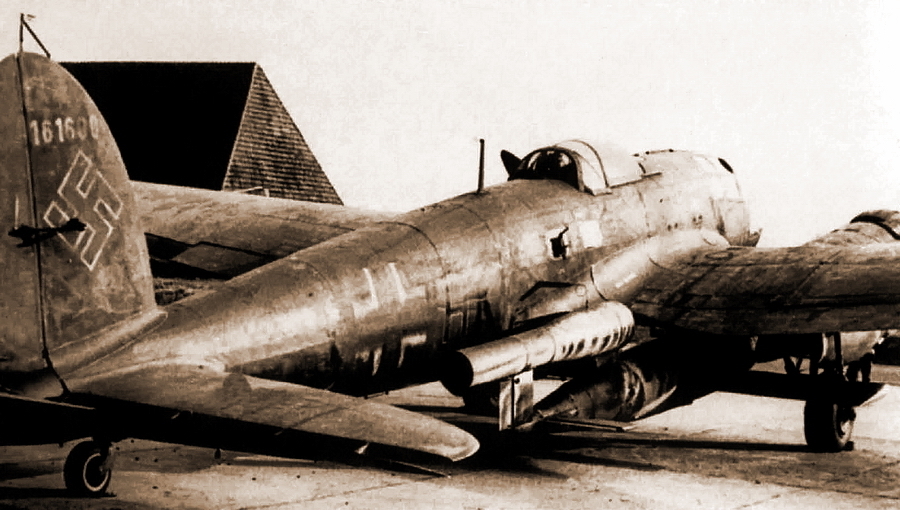

The launch of the Fi 103 from the carrier aircraft was envisaged from the beginning, but practical launches were delayed. It was not until June that the III./KG 3 air squadron arrived on the western front, rearmed with the Heinkel He 111H-22 missile carrier, and during the night of July 8 its crews made their first combat flight under the new assignment and soon reached an intensity of more than 10 launches a day.

The already sluggish Heinkel machines were too vulnerable with suspended missiles, so they could only be used at night. The planes approached the launch area off the Dutch coast of the North Sea at a low altitude, then gained altitude before launch and dived down again immediately after the flying bomb was separated. The experiment was a success and in October, two more groups of the KG 53 squadron joined III./KG 3 which was renamed I./KG 53.

The British acknowledged the new threat somewhat late, as they started to fight the V-1 air carriers as late as August. A total of seven Mosquito squadron crews and No. 501 Squadron of Tempests had joined the hunt by early 1945.

The cruising speed of the He 111 with suspended V-1 bombs was close to the stall speed of the Mosquitoes, so the FIDS (Fighter Interception Development Squadron, formerly FIU) made use of the then somewhat obsolete Beaufighter Mk.VIF night fighters to intercept the carriers. At the end of the year, FIDS started practicing the interception of low-flying targets while guiding fighters from the Wellington equipped with the ASV radar. This combination was only used in practice in January 1945, when fighter missions of KG 53 were ceased, so all the marks on British radar screens turned out to be friendly planes.

The Germans fired a total of 1,776 air-launched cruise missiles at England; the last one was fired on the night of January 14, 1945. Of the total, 1,012 buzz bombs were spotted by British radars, of which 11 were shot down by naval artillery, 320 by anti-aircraft artillery, and 73 by RAF fighters. Three hundred and eighty-eight doodlebugs reached England, 66 of them hit the London area.

The final attempts to reach London

In February 1945, the German “anti-aircraft gunners” received new Fi 103E cruise missiles, which in theory had an increased range, sufficient to shell London from the Netherlands. By the end of the month, 21 launch sites had been set up. Between March 3 and 29, 275 missiles were fired at the British capital, only 160 of which traveled any significant distance. Of those, 92 were shot down by the British air defense system, and only 13 reached London, the last one on March 28.

The same fighter squadrons that hunted for air-launched missiles, as well as the night fighters of the two tactical air forces credited with the destruction of the last buzz bombs, were involved in interceptions of longer range V-1 bombs. On the night of March 28, the crew of Flying Officer Martin G. Kent of No. 409 Squadron flying Mosquitoes NF Mk.XIII observed four or five rockets launched while on patrol in the vicinity of Arnhem. In a few attacks the British scored two victories. Two days earlier, Fight Lieutenant Albert J. Grottick of No. 501 Squadron won the last victory over the V-1 directly over the British Isles.

Outcomes of the “campaign of retribution” against Britain

In the period from June 1944 to March 1945, the Germans fired 10,668 cruise missiles at British cities. About 2,700 of them successfully penetrated the air defense system, killing more than 6,000 people and injuring about 18,000. According to official statistics, the British fighter aviation is credited with destroying 1,979 flying bombs, but combined scores of all fighter units gives a number that is higher by 50–200 (according to various documents).

The Tempest became the most successful interceptor with about 800 victories and the top two highest-scoring squadrons, the top two aces and seven of the top ten. The night Mosquitoes performed a little worse, with about 500 victories, the fourth most successful squadron, and ace number three. The Spitfires and Griffons accounted for about 400 victories, third and fifth most successful squadrons. The Mustang ranked fourth, and the Spitfire Mk.IX fifth. Other types of fighters had little effect on the statistics.

Victories over flying bombs were counted according to the same rules as shot planes, but separately. Otherwise the list of the best anti-Hitler coalition aces would have looked very different, because best anti-Diver squadron leader Joseph Berry, who served first in the Tempest flight of FIU and later commanded No. 501 Squadron, scored 59.5 victories over “robots” (including 28 night victories) and had only one downed airplane. Two more pilots had almost 40 victories each, and ten had between 20 and 30 V-1 destroyed.

V-1 over Antwerp

Great Britain was the most prominent, but not the only target of V-1 flying bombs. In October 1944, following Hitler’s personal orders, the bombing of Antwerp, a strategically important point in the Allies’ supply chain on the continent, started. On October 7, ballistic missiles were launched, while V-1 bombs were shot at that target starting October 21. The Germans fired 11,988 cruise missiles at Antwerp, Brussels, and Liège altogether — more than they had fired at England. The last launches were reported in the evening of March 27.

The Allies relied entirely on anti-aircraft artillery to defend Antwerp. Their fighters did not specifically hunt V-1 buzz bombs, but they naturally attacked them whenever they encountered them accidentally. Victories over doodlebugs are credited to pilots of various squadrons of the American 9th Air Force and RAF Second Tactical Air Force, but those were scarce and made little contribution.

Drawings by Mikhail Bykov