The Berlin events of the fall of 1961 were arguably one of the most severe crises of the Cold War. One would have thought the Soviet leadership’s decisive break from Stalinism would have empowered the USSR to finally reach the same wavelength with the United States. However, the hard lines of their respective leaders and lack of trust and understanding brought the two superpowers to the brink of military confrontation.

The Berlin Issue

Since the end of World War II, Berlin had unwillingly served as a symbol of divided Europe.

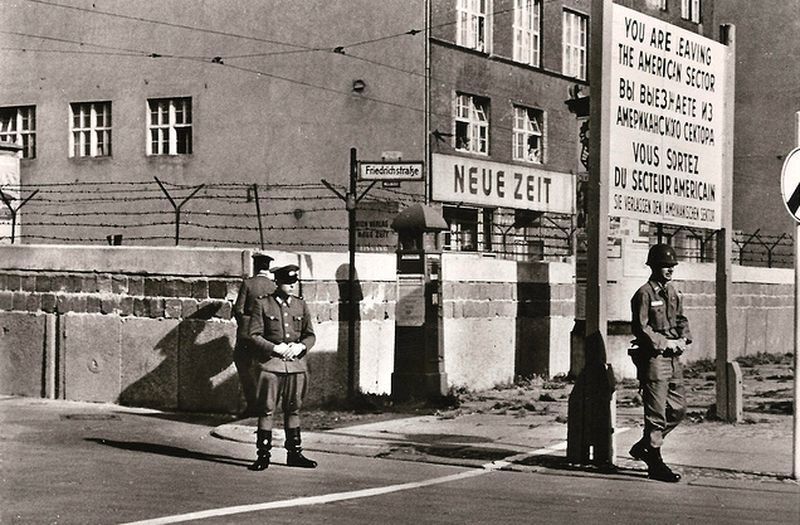

Under agreements between the powers that defeated Germany Berlin was divided into four occupation sectors. During the first decade and a half after the war, the western part of Berlin, controlled by the U.S., the UK, and France, became an island of free world inside the German Democratic Republic (GDR), a showcase of western prosperity amidst the miserable life of the communist bloc, whose lights beckoned tens of thousands of East Germans.

The Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), which experienced the “economic miracle”, boasted a per capita income twice that of the GDR. Car output was eight and a half times higher, and West German marks were exchanged for the East mark at a rate of one to five.

Thousands of residents of the GDR “voted with their feet”, benefiting from the absence of border controls. It was enough to come to Berlin, take the subway and go to one of the Western sectors, where you could apply for emigration. In 1959, 140,000 citizens of the GDR fled to the West; in 1960, 185,000 followed suit, that is, 500 people every day. In a letter to Khrushchev on January 18, 1961, the East German leader Walter Ulbricht estimated the total number of GDR citizens who fled to the West during the previous decade to be 2 million.

In addition to the economic achievements of the FRG, the East was increasingly concerned about the vigorous military buildup. Armed with modern weaponry, the Bundeswehr became one of the most powerful armies of NATO with up to 291,000 personnel (nine divisions).

Diplomatic offensive

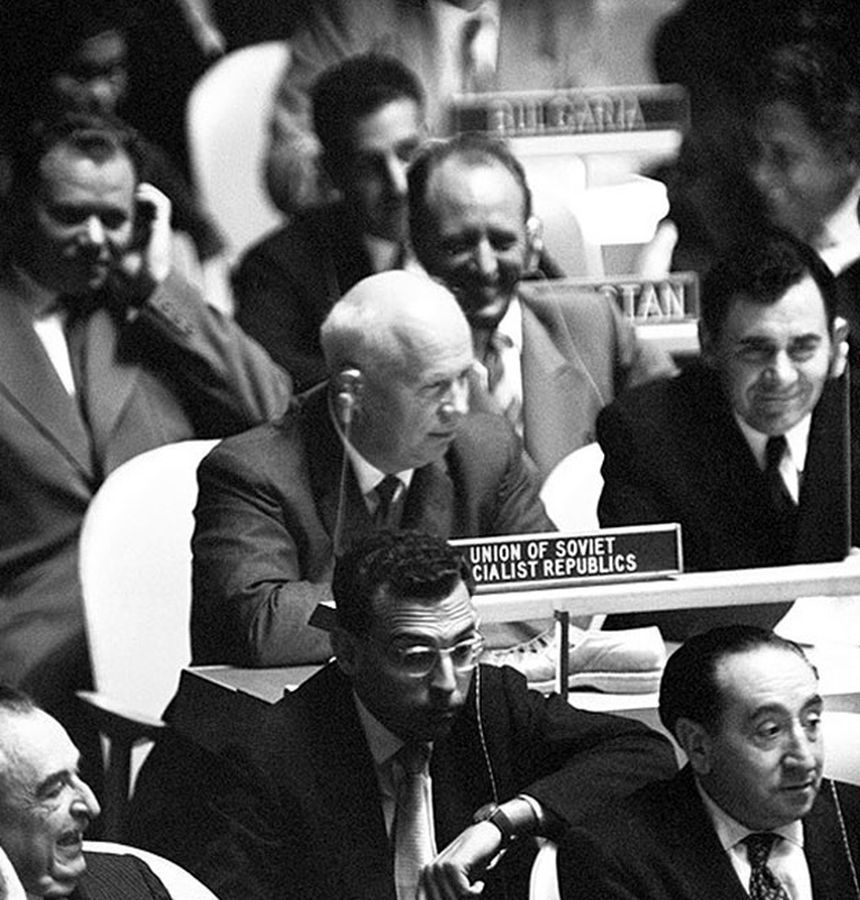

The Soviet leadership first raised the question of changing the postwar status of Berlin on November 10, 1958, when, completely unexpectedly for the West, Nikita Khrushchev, Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers and First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, said at a meeting with a delegation of Polish communists in Moscow:

“The time has obviously arrived for the signatories of the Potsdam Agreement to renounce the remnants of the occupation regime in Berlin and thereby make it possible to create a normal situation in the capital of the German Democratic Republic.”

Two weeks later, the Soviet leader’s statement was presented to the Western allies in the form of an official note, which invited them to recognize the Potsdam Agreement on the status of Berlin to be no longer in force. If no agreement were to be reached within six months, the USSR was going to sign a unilateral peace treaty with the GDR and transfer control of the city to its East German allies.

According to Khrushchev, West Berlin was “a bone stuck in the throat” of the Soviet Union, and he wished to remove that bone by making Berlin a demilitarized “free city” under the supervision of representatives of the United Nations. The 1955 agreement defining Austria’s neutrality could have served as a model for the status of the German capital.

Khrushchev reassured his fellow party members by claiming that the U.S. would not start a war over Berlin. He was saying that his aim was simply to compel the U.S. to agree to start negotiations on Berlin and embark on a diplomatic process of “incessant exchanges of notes, letters, declarations, and speeches.” And this process was indeed set in motion, albeit with no tangible results over several years. The West defended its position of maintaining the status quo in Berlin.

Attempted dialogue in Vienna and new aggravation

Moscow pinned its hopes for a change in the U.S. position on the Berlin issue on the newly elected president, John F. Kennedy, who took office on January 10, 1961. A series of statements made by the new president, as well as the events surrounding the failed attempt to overthrow Castro in the spring of 1961 (the Bay of Pigs invasion), convinced the Soviet leader that he was dealing with a weak and inexperienced opponent. The leaders of the two superpowers met in the Austrian capital of Vienna on June 3–4, 1961.

While Kennedy sought to discuss alternative issues (such as the situation in Angola and Laos, a nuclear test ban, or the coordination of the space programs), Khrushchev kept getting back to the Berlin issue.

“Berlin is the most dangerous place in the world. The Soviet Union wants to perform an operation on this sore spot – to eliminate this thorn, this ulcer.”

the Soviet leader told his American counterpart. Kennedy tried to respond in as conciliatory a tone as possible:

“Conditions in many parts of the world are not satisfactory, and it is not the right time to change the balance in Berlin or in the world more generally. If this balance should change, the situation in West Europe as a whole would change, and this would be a most serious blow to the U.S.”

As a result, Khrushchev set another six-month deadline for an agreement on Berlin, saying:

“If the U.S. refuses to sign a peace treaty, the USSR will have no way out other than to sign such a treaty alone, and nothing will stop it.”

The situation was further exacerbated by the June 16 plenary session of the Bundesrat, the upper house of the German parliament, in West Berlin. In response, the East German leader, Walter Ulbricht, declared his intention to put an end to the existing “so-called refugee camps” in West Berlin as soon as possible.

Khrushchev attended the meeting celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the beginning of World War II wearing the uniform of a lieutenant general complete with decorations, which was very seldom the case. He spoke about the results of the Vienna meeting and referred to the West’s refusal to compromise on the Berlin status as a threat to the entire communist world. He declared that the West, like the Nazis twenty years earlier, would be defeated by the armed forces of the Soviet Union and the socialist camp.

One after another, prominent Soviet military commanders praised Khrushchev for his leadership and warned about the danger stemming from Berlin. Marshal Vasily Chuikov, commander-in-chief of the Soviet Union’s ground forces, said:

“The historic truth is that during the assault on Berlin there was not a single American, British or French armed soldier around it.”

It turned out that the western allies’ claims to special rights in Berlin are “entirely unfounded.”

On July 15, 1961, in Miami Beach, a city far from Europe, 24-year-old blonde Marlene Schmidt, a trained engineer, who had fled to the West from the GDR the year before, was crowned Miss Universe. This fact, seemingly so distant from politics, provoked a powerful outburst of propaganda warfare.

The western press seemed to have entered a sarcasm competition, mocking the communists, from whom such beauties were fleeing. East German newspapers denounced a capitalism in which “only the bust, waist, and hips matter”, and accused the Americans of rigging the results of the pageant in order to create the myth of “Cinderella from the Soviet Zone.”

The erection of the Wall

On the night of August 13, 1961, numerous patrols of the East German police and factory militia men installed wire fences along the entire border with West Berlin, which over the following weeks were rapidly replaced by a concrete wall. Border control was introduced between the two parts of the city.

A statement by the Warsaw Treaty Organization member states said that in order to prevent revanchists, extremists, saboteurs and spies from entering the GDR,

“reliable safeguard and effective control will be established around the whole territory of West Berlin.”

To support these actions, three Soviet and two East German divisions surrounded Berlin. The 81st Guards Motorized Rifle Regiment from the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSFG) was deployed in the city.

The operation, which few believed was real, including those in Western intelligence, had been prepared in deep secrecy and was carried out all at once at lightning speed. The barbed wire had been purchased by East German agents in small batches in Germany and Britain during the previous couple of months. The operation itself was led by the future GDR leader, Erich Honecker, the secretary of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), who was responsible for national security.

Over the next three decades, the city was divided. The subway service between the western and the eastern parts of the city was halted. Where the border ran through residential buildings, windows and doors leading westward were bricked up.

East Germans never gave up their attempts to leave their country, but it was now much harder to succeed.

On August 22, Ulbricht announced the creation of a 100-meter neutral zone along the Wall, in which East German police officers would be allowed to shoot to kill. A couple of days later, the statement was corroborated by action – on August 24, a 24-year-old tailor, Günter Litfin, was shot dead while trying to flee to the West, becoming the first of hundreds of victims of the Wall.

Escalation

At 11:00 on August 13, 1961, Allan Lightner, the top-ranking civilian official at the U.S. Mission in Berlin, notified Washington that

“the East German regime has taken harsh measures resulting in the closure of entry to West Berlin to residents of the Soviet zone and East Berlin.”

President Kennedy’s first reaction to the news from Berlin was his famous phrase: “A wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” Nevertheless, he took a number of steps designed to demonstrate the U.S.’ determination to defend West Berlin.

Retired General Lucius D. Clay, the hero of the 1948 Berlin Airlift, was dispatched to Germany as the President’s Special Representative in Berlin.

On August 20, the first reinforcements – 1,500 American soldiers – arrived in West Berlin. The Soviet side made no attempt to obstruct their movement along the highway running through East German territory.

The U.S. Congress voted for an additional military appropriation of USD 3.247 billion, an increase in the army size to 1 million from 875,000, a 29,000 increase in Navy personnel and 63,000 increase in Air Force personnel. National Guard and Reserves were additionally called, and mothballed warships and B-47 bombers were reactivated. President Kennedy’s National Security Council meetings discussed plans for a nuclear war against the USSR.

The Soviets retaliated. On August 29, transfers of Soviet army personnel to the reserves were suspended. On August 30, Khrushchev announced the end of the three-year moratorium on tests of nuclear weapons. Two days later, the first in a series of nuclear explosions was conducted, culminating in the detonation of the 50-megaton Tsar Bomba on Novaya Zemlya on October 30.

On October 17, 1961, in his speech at the opening of the 22nd Congress of the CPSU, Khrushchev unexpectedly declared that he would not insist on having a peace treaty signed to address the Berlin issue by the end of the year, because during diplomatic consultations the West showed its willingness to resolve the problem through negotiations. One would have thought that after such a statement the crisis would finally be resolved. But it is immediately after that statement that the tensest events of the Berlin confrontation took place around Checkpoint Charlie.

The Checkpoint Charlie crisis

On the evening of October 22, senior American diplomat Allan Lightner and his wife were on their way to an East Berlin opera house. At the border his car was stopped by East German policemen who requested to see his documents.

Lightner refused – the Potsdam agreement did not entitle Germans to check Allies’ documents – and demanded that a Soviet representative be summoned. However, the German said he could not be reached on Sunday evening.

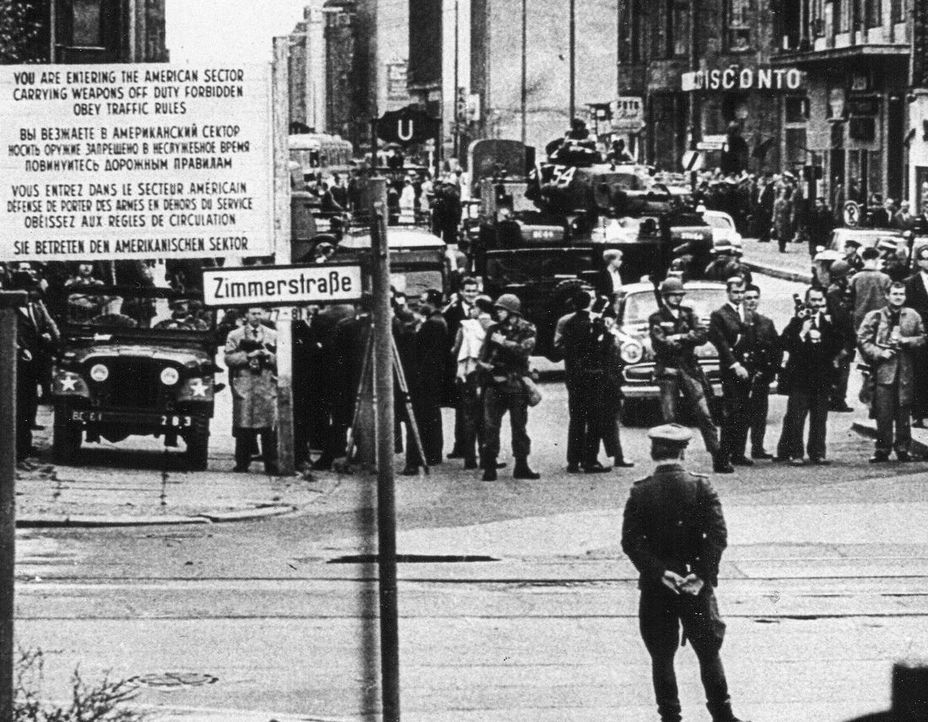

When he learned about what had happened, General Clay immediately sent four M48 Patton tanks to Checkpoint Charlie. As soon as they stopped on the American side, the tanks aimed their guns at the East German border guards. Two groups of four U.S. military policemen wielding M-14 rifles with fixed bayonets approached Lightner’s vehicle from each side.

The diplomat then drove to East Berlin and turned around at the next intersection to go back (he was already late for the opera anyway). After a while, Colonel Lazarev, assistant political advisor to the head of the GSFG, appeared at the checkpoint and apologized for the behavior of the East German border guards. It seemed that the incident was over.

However, on October 23, East German radio broadcast a decree adopted by the GDR authorities that all foreigners – except the military wearing uniforms – were required to present documents when entering “democratic” Berlin. In response, General Clay received orders from Washington to continue the practice of “armed escorts”.

Four of the Patton tanks involved in those demonstrations were equipped with bulldozer shovels, which put the Soviet side on the alert lest the Americans should try to demolish the border barriers. Such concerns were reinforced by the photographs obtained by Soviet intelligence featuring the September exercises of American tankers in the woods on the outskirts of Berlin, where they practiced breaking through a wall.

On the afternoon of October 25, General Albert Watson, the commandant of Berlin, met with his Soviet counterpart Colonel Andrei Solovyev. Watson demanded that the Soviets take immediate action to stop the East Germans from violating the Potsdam Agreement. Solovyev responded that Americans’ sending armed soldiers across the border was an “open provocation” and a direct violation of the GDR laws. He confirmed that U.S. military personnel could visit East Berlin freely, but only if East German border guards had no doubts about their nationality – hence the requirement to produce documents.

Watson begged to differ, though, and said that the U.S. intended to continue taking all necessary measures to ensure free access of its representatives to East Berlin. Solovyev warned him against “acts of provocation” citing possible retaliation. “We have tanks, too,” the Soviet colonel said at the conclusion of an hour-and-a-half-long negotiations that turned out to be fruitless.

Over the next couple of days, U.S. tanks continued making regular trips to Checkpoint Charlie, whereas U.S. marines escorted diplomats passing to the east side.

This was also the case on Friday, October 27, 1961.

The most dangerous hours of the Cold War

At 16:45, after completing another “armed escort”, the M48 tanks were heading back to their base at Tempelhof Airport. Major Thomas Tyree, a company commander of the 40th Tank Regiment, along with Lieutenant Vern Pike, platoon leader of the military police, went into a pharmacy near the checkpoint to get warm.

Suddenly they heard the roar of tank engines. As they stepped outside, they saw 10 tanks parked a hundred meters away on the Soviet side of the border. They looked like new Soviet T-54, but were unmarked.

Major Tyree immediately ordered his tanks to return, and at 17:25 ten Patton tanks stopped at Checkpoint Charlie on the U.S. side.

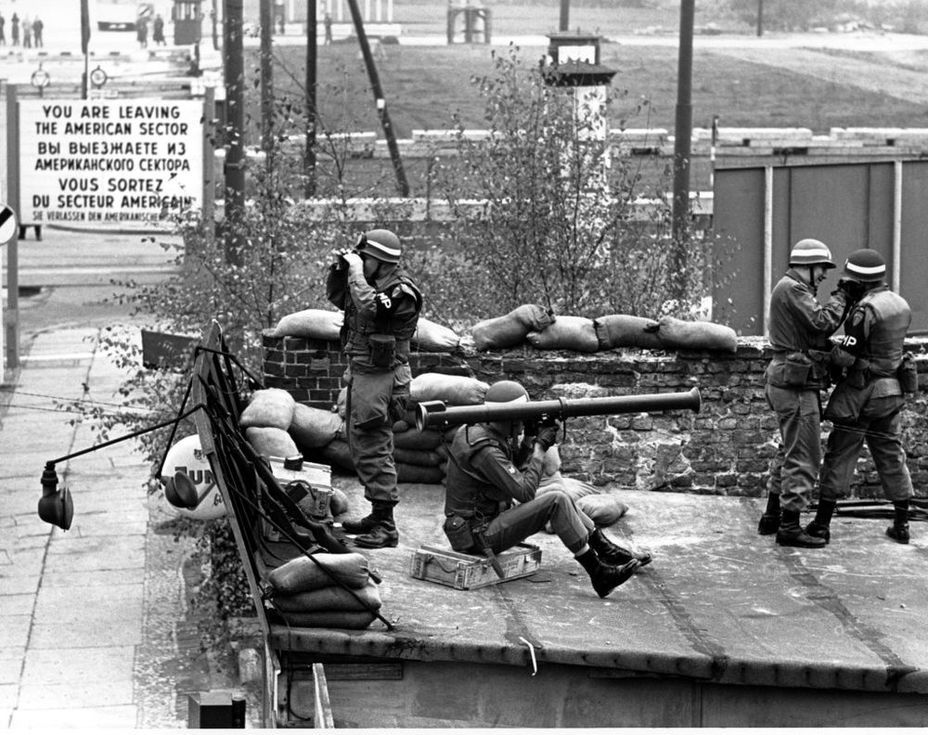

A large crowd of onlookers gathered at once, and many journalists arrived. U.S. military police reinforcements came in five APCs under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Sabolick and took up positions on the street and rooftops near the checkpoint.

Twenty-three more T-54 tanks drove through the Brandenburg Gate and stopped in Berlin’s main boulevard, Unter den Linden. In response, the remaining tanks of the 40th Regiment were ordered to move from Tempelhof to be ultimately positioned in the yards of the houses adjacent to Checkpoint Charlie.

Captain Voitchenko’s 7th tank company, 3rd battalion, 68th guards tank regiment, was involved in the events on the Soviet side. Company sergeant V. Sychev recalled:

“American M-48 tanks are standing in front of us. To the left of the tanks, in the windows and in the attic of the border station, behind sandbags, armed policemen took positions, and to the right – the hooting and whistling crowd of fascist youths.”

A new world war could have started not based on orders from Moscow or Washington, but simply by accident if any of the tankers had lost their nerve.

CBS Radio correspondent Daniel Schorr made an acid comment on the lack of identifying marks on the T-54 tanks:

“Or we may one day hear that they were just Russian-speaking volunteers who had bought some surplus tanks and come down on their own.”

But General Clay demanded irrefutable proof from his subordinates that it was Soviet military hardware they were up against. Under cover of darkness, Lieutenant Pike and his driver, Sam McCart, drove to the Soviet side and parked at the last tank in line. Since the tankers had left the vehicle, the lieutenant climbed inside, where he found Cyrillic inscriptions and a copy of Pravda newspaper. The Americans returned to their side, bringing the newspaper as proof that the tanks were Soviet. Lieutenant Pike later recalled that most of the Soviet tankers were Asians.

Allied garrisons were put on the alert. A unit of British infantrymen with two anti-tank guns took up positions at the Brandenburg Gate.

The cold night at Checkpoint Charlie was filled with suspenseful anticipation, as the air was shaking with the rumble of tank engines.

In the meantime, an intense exchange of messages between Moscow and Washington was underway. Decisive agreements were reached during a night meeting between U.S. Secretary of Justice Robert Kennedy (the president’s brother) and Washington GRU resident Colonel Georgi Bolshakov.

Neither took notes of their conversation, so the details of the meeting are unknown. But from that moment on, the Americans discontinued their “armed escorts”, whereas the East Germans stopped requesting documents from the Allies.

At 10:30 on October 28, 1961, the Soviet tanks pulled away from Checkpoint Charlie; half an hour later, the American tanks headed for their base as well.

One of the most dangerous days of the Cold War was over.

Conclusion

As General Brent Scowcroft, U.S. National Security Advisor under President Gerald Ford and then under George H. W. Bush, wrote a lot later,

“the events of 1961 put the Cold War back into a deep freeze at a time when Khrushchev’s break with Stalinism might have presented us with the first possibilities of a thaw.”

The lack of understanding of the decision-making mechanism in the adversary’s camp, misinterpretation of the other side’s actions, personal fixations and ambitions, as well as misconception gradually brought the two superpowers to the brink of a war that no one wanted. A year later, the same set of reasons led to an even more dangerous scenario, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Frederick Kempe, a renowned American journalist, president of the Atlantic Council, a U.S. foreign policy think tank, and the author of the bestseller Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth, writes:

“The Cuban crisis would never have happened if Kennedy had been more decisive during the Berlin crisis. Kennedy allowed Khrushchev to build the Berlin Wall and cut East Germany off from West Germany hoping that the Kremlin would correctly interpret Washington’s peaceful intentions and agree to bilateral cooperation by abandoning the nuclear arms race. But Khrushchev perceived this as weakness, indecision, and even cowardice from the U.S. president. So Khrushchev decided that Kennedy would eagerly swallow the next pill: Soviet missiles in Cuba.”

President Kennedy must have been aware of this as he wrote to British Prime Minister Macmillan at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis:

“What is essential at this moment of the highest test is that Khrushchev should discover that if he is counting on weakness or irresolution, he has miscalculated…”

On June 27, 1963, speaking to tens of thousands of West Berliners, President John F. Kennedy uttered his famous words:

“All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and, therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’.”

Sources:

- Frederick Kemp. Berlin 1961. Kennedy, Khrushchev and the most dangerous place on Earth — Centerpolygraph, 2013;

- Henry Kissinger. Diplomacy — M .: Ladomir, 1997;

- Lavrenov S. Ya., Popov I. M. Breath of the «hot» war in Europe, 1958–1962. // Soviet Union in local wars and conflicts. — M .: Astrel, 2003;

- A. A. Fursenko. Georgy Bolshakov — Khrushchev's liaison with President Kennedy // Zvezda, 1997 — № 7.