Nowadays, a pilum as well as a gladius is firmly associated with a Rome legionary image. This kind of a javelin was intended for throwing at an enemy from the distance. So how did warriors use it and how effective this vivid weapon was in a battle? Not only written sources could give us the answers, but also modern reconstructions.

On numerous pictorial monuments, among which Trajan's Column specially stands out, a pilum looks like a heavy dart, the size of which slightly exceeds a human height. The archaeological finds of a pilum are most often a four-sided iron rod about 0.5 m long with a hard pyramidal tip from one end and another one is flattened into a tang with two holes. With the help of a wooden block and two rivets, the flat end was connected to a shaft. In a lighter pilum variant, the rod was mounted on the shaft with a simple socket. Modern pilum reconstructions have a weight of 1.7 kg.

The origin

The word “pilum” itself means “a pestle” in Latin. Probably, in the beginning that was just a weapon nickname that had been given for some shape similarity. However, there are other hypotheses of the origin of ‘pilum” etymology. For example, Roman grammarian Festus quoted a very ancient hymn text of the Salian priests, in which the Roman people was called “pilumnoe poploe” — something like «the spearmen people». In addition to the usual “pilum”, there were other known names of the weapon. For instance, in the Sibian language, that occurred in the central part of Italy, “pilum” was called “verum” or, later, “verutum”. The Greeks called the Roman pilum ΰσσος that probably originated from Gallic γαισος – “geza” that meant Gallic weapons of a similar kind.

The Romans adopted a pilum as a weapon in the second half of the 4th century or in the beginning of the 3rd century BC, taking its design from the neighbors. According to Livy and Pliny the Elder, those neighbors were the Etruscans, Plutarch and Propertius called the Sabines, Vatican Anonymous — the Samnites, Athenaeus — the Iberians. Such a discrepancy in determining the origin place indicates that for many years neither the Romans nor the Greeks themselves had the accurate information about it. It is noteworthy, that the Greeks, as it has been already said, called a pilum the word “geza” that had a Gallic origin. Moreover, the Romans willingly compared a pilum to such species of Gallic javelins as falarica, tragula, grosphos or a soliferrum. Perhaps these parallels are able to cast light on the problem of the pilum origin better than the etymology of the name.

Partly, the archaeology might come for help here. Pilum-like socket weapon with a long iron rod and a flat or pyramidal tip could be met already in the 4th century BC as a part of Gallic burial grounds inventory in Monte Bibele and Montefortino in the northern Italy. The parallels are also known with the weapon that was found as a part of offerings or in burial grounds on the other side of the Alps. Etruscan materials are similarly interesting, because they include a sample of a socket “pilum” tip 1.2 m long from Vulci and it is absolutely identical to the above-mentioned Gallic finds from Monte Bibele and Montefortino that are likewise dated the 4th century BC. Besides that, there are “pilum” images on the painting of the Giglioli tomb at Tarquinia among other weapons, including round hoplite shields and sheathed swords that are as well related to the 4th century BC.

The description and finds

The Greek historian Polybius provided the first Roman pilum description in the middle if 2nd century BC:

“The javelins (ΰσσοι, that is, he is talking about the pilum) are of two sorts – stout and fine. Of the stout ones some are round and a palm’s length in diameter (77 mm) and others are a palm square. Fine pila which they carry in addition to the stout ones, are like moderate sized hunting-spears, the length of the half in all cases being about three cubits (1,38 м). Each is fitted with a barbed iron head of the same length as the haft. This they attach so securely to the haft, carrying the attachment halfway up the latter and fixing it with numerous rivets, that in action the iron will break sooner than become detached, although its thickness at the bottom where it comes in contact with the wood is a finger’s breadth and a half (29 mm).”

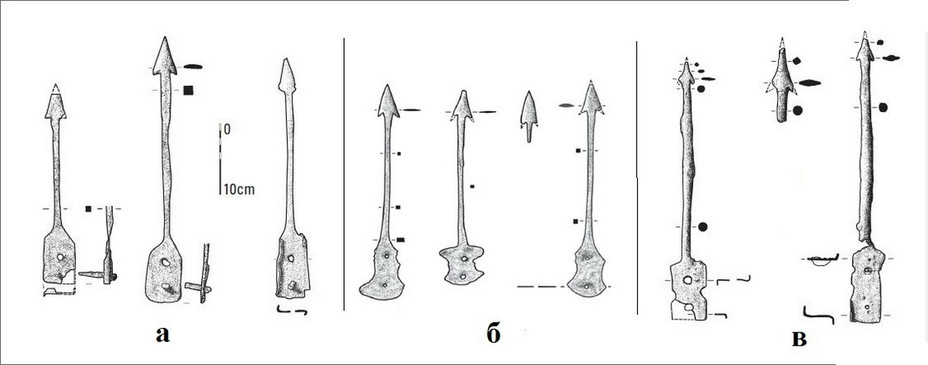

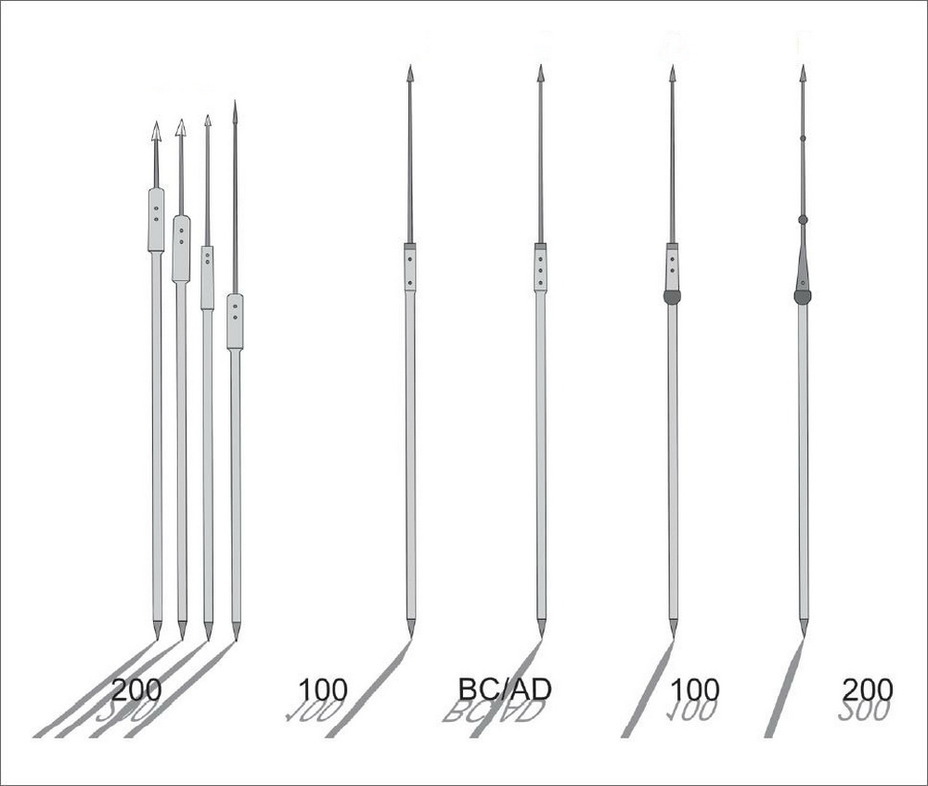

This description corresponds to original archaeological finds of pilum heads dated 3rd–2nd centuries BC from Talamonaccio in Italy, Castellruf in Spain, Šmihel in Slovenia and Ephyra in Greece. The finds from Talamonaccio are the earliest among them and they are connected with the famous battle fought between the Gauls and Romans near Telamone in 225 BC. They are all a relatively short (between 27 and 32 cm) shank with a barbed triangular head and a wide flat tang with two through holes for rivets, with the help of which all the iron parts (head, shank and tang) were secured to the shaft. Castelruf finds are very similar to them in shape but they possess a little bit larger (between 27 and 41.7 cm) sizes. The hoard from Šmihel contained several dozen socketed shanks that belonged to a light pilum variant. They varied between 20 and 38 cm in length. Unlike the previous model, socketed pila were equipped with a pyramidal shape tip.

The pila of the Late Republican period (the 1st century BC) were distinguished by a larger size. The iron part length of the pilum of the second half of the 2nd century BC, found in Renieblas (Spain), already was 74 cm. The Spanish finds from Valencia and Osuna have similar proportions. The former refers to the Sertorian War (82-72 BC), the latter — to the final Caesar’s company in Spain and to the Battle of Munda (45 BC).

The important pilum peculiarity of that time was the disappearance of flat wide tips that were widespread earlier. A pyramidal shape tip witnesses of the increased armor – piercing weapon function, the hit of which should pierce both a wooden shield and and the armored bearer of the shield. The effective task fulfillment is directly related with the solidity of the weapon wooden and iron parts joint. That makes one doubt in a funny tale told by Plutarch as if Marius thought out to change an iron rivet, with the help of which a pilum tang joined a shaft, onto a wooden nail. The nail broke when a pilum got into an enemy’s shield and the weapon was out of order and it was impossible to hurl it back.

Meanwhile, Polybius wrote about the attention the Romans pay to the solidity of a pilum shank and its shaft joint. The curved edge of the shank flat part should serve the same solidity goal in all the finds of heavy pila of 3rd-1st centuries BC. The edge embraced the wooden shaft mount and prevented the pilum shank fall if a rivet broke.

The effectiveness

In “Commentaries on the Gallic War” Caesar brightly described the effect that pilum volleys made on the ranks of the Roman’s foes:

“The legionaries, from the upper ground easily broke the mass formation of the enemy by a volley of pila (…) The Gauls were greatly encumbered for the fight because several of their shields would be pierced and fastened together by a single pilum; and as the iron became bent, they could not pluck it forth, nor fight handily with the left arm encumbered. Therefore, many of them preferred, after continued shaking of the arm, to cast off the shield and so fight bare-bodied.”

One more vivid description belongs to Livy:

“On Legates’ order, warriors picked up spears, that dotted the ground between the armies and hurled them into foe’s “tortoise”; many spears plunged shields and some even enemies’ bodies and their mass formation was broken, moreover, a lot of people fell down, not even wounded, but only stunned.”

As it is seen from the descriptions, the pilum hit had such a great penetrating power that neither shield nor armor could survive it. English historian Peter Connolly in 1998 and in 2002 conducted tests with several modern replicas of the weapon. He tested heavy pila with wide head of Talamonaccio type (1.280 kg) and a model with a pyramidal shape head of Renieblas type (1.710 kg) and also a series of lighter pilum models of Šmihel type (1.110 kg) and a light dart (0.230 kg). When testing the throw range, the best results looked like this:

- Talamonaccio type – 34.8 m;

- Renieblas type – 33.7 m;

- a light dart – 54.5 m.

The next test was on a penetration capability. An 11 mm thick three-layer plywood sheet was used as an aim. The dart did not penetrate the plywood shield, when it struck, its tip always bent. Talamonaccio type with its wide triangular head was not able to pierce the sheet either. Renieblas type pierced the shield through and as the test author noted it was very hard to pluck it forth — the edges of the hole closed around him. When faking on the ground the pilum iron slightly bent in the full accordance with the descriptions in narrative sources.

The technique of use

Caesar’s description of the Battle of Pharsalus clearly reveals the application order of the weapon by the Roman legionaries:

“There was exactly as much space between both troops as was necessary for a mutual attack. But Pompey ordered his men to receive the charge from the Caesar’s side and fight defensively in order to let their front stretch. They said, Pompey's adviser Gaius Triarius believed that Caesar's infantry would be fatigued and fall into disorder during the first violent onslaught, the front would stretch and only then, his soldiers would attack the scattered enemy units in closed ranks. Meanwhile, he hoped that enemies’ javelins would inflict less damage if his soldiers would remain in the ranks than if they moved to face enemies javelin volleys; at the same time, Caesar’s legionaries would have to cover twice the distance to reach them and would arrive winded and entirely exhausted (…)

Caesar’s men, when the signal was given, rushed forward with their javelins ready to be launched, but perceiving that Pompey's men did not run to meet their charge, and having acquired experience by custom and practice in former battles, they of their own accord repressed their speed, and halted almost midway, so that they would not come up with the enemy when their strength was exhausted; after a short respite they renewed their course, threw their javelins, and instantly drew their swords, as Caesar had ordered them. Nor did Pompey's men fail in this crisis, for they received javelins, stood the charge, and maintained their ranks; and having launched their javelins, had recourse to their swords.”

The presented picture means that a foe was attacked from somewhat distance, going from a step to a run at this moment. At centuriones’ signal and according to their personal experience, warriors showered the enemy lines with their pila and after that attacked them with swords in their hands. With the whole scheme simplicity, it causes questions. Scientists argue about how and from which distance the hurl was performed. Although, as we could see, it was proven experimentally, that one could throw a pilum at a distance of about 30 m and almost certainly, the hurl was usually performed from a much shorter distance. The interval between 18 and 10 meters from a foe looks as the most acceptable variant: the weapon still possesses a great penetrating power and a warrior has enough time to throw a pilum and snatch his sword to get ready for hand-to-hand melee.

There exists a series of scenarios describing the way pilum hurl could be performed. According to the first one, the whole unit throw pila at once. The advantage of this method is a high missile concentration on a relatively narrow front sector that resembles the above-mentioned Livy’s quote. In practice, the scenario is hard to perform as the last warrior line is separated from the first one at a distance of about 9 m and it is hardly capable of pila throwing at foes without the risk to hurt legionaries from the first line.

According to another scenario, warriors hurl their pila by lines or even one by one instead of “do it all together” and thus approach foe lines at a certain distance. At last, one more variant is a scenario when pila are thrown by the warriors of the first two or three lines and the rest throw their missiles later – either by themselves or pass the weapons to front lines.

A throwing combat

Nowadays nearly all the researchers recognize that battles could have long breaks when both sides first converged, and then diverged in order to have rest, clean themselves up and replenish the stock of weapons. Caesar described such a type of combat in the Battle of Ilerda during the Spanish Civil War in the summer of 49 BC. The warriors of Lucius Afranius, that opposed him, stood on the top of the hill, the only ascent to which did not exceed the width of the deployed front of three cohorts, that is, about 150 m. IX Spanish Legion from Caesar’s army stood by the foot of the hill, bravely tolerated the fire from Afranius side for five hours and sometimes successfully counterattacked. At last, the legionaries ran out of missiles and then Caesar’s warriors undertook a decisive counterattack up the hillside and thus made the enemy retrieve.

It seems that IX Spanish Legion was fully staffed. Consequently, in beginning of the combat the soldiers had around 10 000 pila. In order to run out all of them, Caesar’s warriors should have thrown 2 000 pila per hour that made up 13 pila on each meter of the front during an hour. If we compare this figure with 60 bullets per meter in the Battle of Waterloo, it seems small. However, at the same time, according to the figures given by Caesar, for 10 000 thrown pila, there were 200 enemy soldiers killed and probably 3-5 times more wounded. In other words, around 10% of the throws were effective that gave a much higher performance statistics in comparison with the firearms of Waterloo epoch. And we should take into consideration that the “goals” had shields and wore armor.

Sources:

- Zhmodikov, A.L. Roman infantry tactics in the IV-II centuries BC/ A.L. Zhmodikov//Para Bellum. — 1998. — No. 4. — P.4-13;

- Connolly, P. Pilum, gladius and pugio in the Late Republic / P. Connolly // Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies. — 1997. — Vol. 8. — P. 41–57;

- Connolly, P. The reconstruction and use of Roman weaponry in the second century BC / P. Connolly // Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies. — 2000. — Vol. 11. — P. 43–60;

- Bishop, M.C. Roman Military Equipment from the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome / M.C. Bishop, J.C.N. Coulston. — Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2006;

- Bishop, M.C. Pilum: The Roman Heavy Javelin / M.C. Bishop // Osprey Publishing, 2017;

- Junkelmann, M. Die Legionen des Augustus: der römische Soldat im archäologischen Experiment / M. Junkelmann. — Mainz: von Zabern, 2003.