The harshness of the Ancient Roman discipline became a common concept. Joining the military service, a Roman citizen came out of the protection of the ordinary law and followed the power of a warlord. The army order was imposed by the iron and blood and death waited for discipline violators. Indulgences did not exist even if a culprit was connected with a warlord by kin bonds. That conscious cruelty was one of the main basics of the high combat ability of the Roman Army.

The civil and military valour

The idea fixed among historians about the Romans’ fundamental difference between the civil and military law. The former was in action only on the city territory and it was defined by the letter of the Law. The latter began beyond the first milestone from the city walls and there the will of the warlord reigned supreme. He had absolute power over the bodies and souls of the subordinates. No wonder, the Romans considered fasces to be one of the signs of the power, which were a belted bunch of wooden rods that Lictors solemnly carried in front of a warlord. Outside the city walls, an axe was put inside fasces that symbolized the warlord’s right to impose the death sentence. On the territory of Rome, the capital punishment was limited by the right of provocation i.e. by the possibility of a sentenced to appeal to the people’s assembly. However, when the army marched then the right stopped acting for those who had become warriors.

The common norms of civil life were suspended in Rome after the declaration of war. Courts closed, the people’s assembly quitted gathering, the trade stopped. Even the civil status of warriors was as if alienated: being enlisted in the army citizens were deprived of basic rights and on a warlord’s order they became subjects of imprisoning, corporal punishment or even execution. Such a peculiarity of civil and legal life was willingly used by the Roman Senate that usually introduced martial law during plebian unrests under the first convenient pretext, mobilize all the discontented into the army and thus forced them to submit. Any gatherings or meetings in the army were strictly forbidden on pain of death. On the other hand, the same peculiarity led to the fact that the famous Plebian secessions of 5-4 centuries BC, as a rule, started from an uprising in the army that refused a warlord in submission and after that retired in full order to the Sacred mountain in 3 miles off the City.

The state of emergency and a warlord’s infinite power were over when the army returned from a campaign and entered the city walls. If a campaign was victorious then it took place in the form of triumphal procession: the commander entered the city in a chariot and ascended to the Capitol where he made a solemn sacrifice to Jupiter. He was followed by the warriors in the procession, who served under him and they took the rite of weapon purification. The formal address to citizens “Quirites” served as the sign of transition from military to civil status accepted in Rome. It was considered, that the only word from a warlord’s mouth freed soldiers from their oath. It was namely this appeal that Caesar reasoned the soldiers who rebelled against him in the autumn of 47 BC and demanded his resignation.

“At the beginning of his word, Appian wrote, he addressed them “quirites” rather than “fellow-soldiers”, the appeal served the sign of the fact that the soldiers had been dismissed and they were already simple people. The soldiers who could not tolerate that any more shouted that they repent and asked him to continue the war alongside with them.”

The harshness of fatherly tempers

The Romans considered the so-called “Manlian Discipline” to be the symbol of severe military discipline inherited from the ancestors. It related to 340 BC when a consul named Titus Manlius Imperiosus ordered Lictors to behead his own son who had violated the ban to leave the military ranks and fight against enemies. A similar case happened in 432 BC when the Roman Dictator Aulus Postumius executed his own son under the identical circumstances. However, Livy, telling the story, expressed a cautious doubt in its reality.

In 325 BC a glorious warlord named Lucius Papirius Cursor who fulfilled the duties of the Dictator sentenced to death his Master of the Cavalry Quintus Fabius Rullianus by name who, as the previous youngsters, contrary to the ban joined the battle against foes and won the victory over them. Fabius succeeded to escape from Lictors’ hands and flee from the camp to Rome where he appealed to the people’s gathering. During the heated debates, Papirius managed to insist on his right but according to unanimous request of the gathering that was very inclined Fabius he at last agreed to soften his anger and forgive the misdeed of Fabius.

The example of “Manlian Discipline” was particularly illustrative due to the conflict between the power of a warlord and the paternal right: “Since you, Titus Manlius, respect neither the consular authority nor the paternal one…» — Livy puts such words into the commander’s mouth enraged by the son’s misdeed. His harshness that became a legend already in the antiquity should become an instance of the wordless submission to discipline, which would stand higher than any circumstances including the paternal affection to children. The tradition of the blind order submission was so indisputable that any personal unauthorized deed even at first sight successful considered in the Roman Army to be the same discipline violation as the failure to comply with the order. No doubt, the instance really served an important landmark for many generations of the Romans, with which they checked their actions both in private and state life. “The Republic of the Romans is strong and powerful by the customs of their ancestors” – wrote a Roman poet Ennius.

The cruelty and intimidation

Both Polybius and other Greeks described severe orders that were in forth in the Roman Army. Rarely in any other states, Polybius noted, the guilty in discipline violation and pusillanimity were treated with such cruelty and contempt as the Romans did. It is known that the Senate repeatedly refused to ransom warriors that had been captured by the enemies. When King Pyrrhus freed Roman captives without any ransom the Senators ordered to transfer those who previously served in the cavalry to infantry and the former infantrymen to auxiliary slinger squads. Neither of them had a right to bivouac inside a camp for the night or sleep in tents and they could only return to the previous service by delivering the armor taken from two killed enemies. The legion soldiers defeated in the Battle of Cannes were moved to Sicily where they were to remain until the end of war with the same ban to camp out and the wheat bread was replaced by barley bread for them.

The Romans applied especially severe punishments for the position abandoning and desertion. The death was the punishment for such crimes and quite often even the extermination of entire detachments did not stop the Romans. It is a known accident when a Campanian legion mutinied and siezed the city of Rhegium in southern Italy during the war against Pyrrhus. The major part of Campanians perished and no more than 300 men were captured. All of them were sent to Rome in chains. Here they were flogged on the Forum and after that, every one of them was beheaded. The Senate resolution required to leave the bodies of the executed without burial and even their relatives were forbidden to mourn them.

Sometimes the Decimation was used in squads retreated under the onslaught of the enemy. In this case, the general formation of troops was made and every tenth was chosen by lot among the escapers who was executed at once. The squad itself was disbanded and its warriors were spread among other Army units.

The camp justice

It was not only a warlord who obtained the discipline power but also tribunes, prefects of the allies and centurions. They had a right to impose penalties, arrest the guilty and flog them. What concerned the responsibility for one or the other crimes, Cato the Elder wrote that the right hand was cut off to those who had been caught stealing from comrades and if one wanted to impose an easier punishment on them then they were whipped in front of the formations. Polybius listed the following misdeeds:

«The Romans regard as cowardice and shame the deeds of the following kind: if someone falsely ascribe a valour feat to themselves in front of tribunes, if somebody out of cowardice leaves his post to which they were put on or also out of cowardice dump some weapons in the heat of a battle (…) Those are also subjects of punishment who steal anything from a camp, who were punished thrice for one and the same crime as well as a young man guilty of sodomy. Such are the deeds that are punishable as crimes by the Romans».

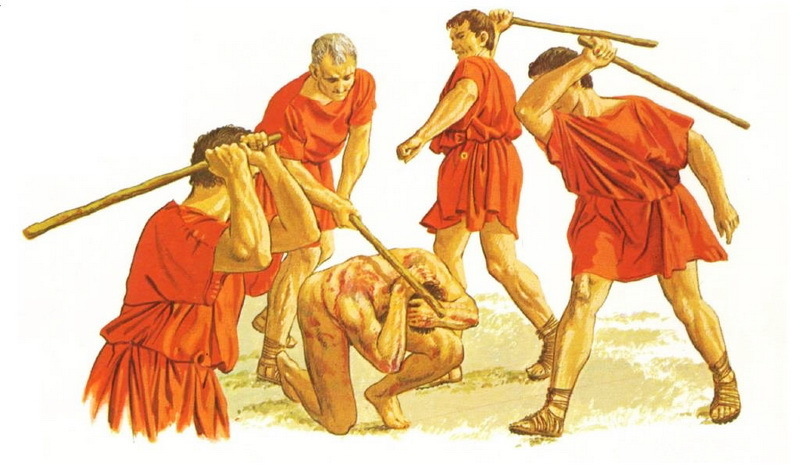

The guilty in those crimes underwent the punishment by clubs (fustuarium) that was carried out by soldiers themselves who often were the comrades and fellow soldiers of the sentenced. After pronouncing a verdict, a tribune took a club and touched the offender with it, after it, soldiers clubbed and stoned him, mostly to death. If still he remained alive then he was exiled and had no right to return home. According to Polybius’s words, the fear of unavoidable punishment made Roman soldiers stand firm at their post even in front of overwhelming in numbers opponents. If they lost a shield or a sword in the heat of a battle, they threw themselves at the enemies’ ranks as if they were berserk in order to get back the losses or die a glorious death. In their minds, only the death on a battlefield could in this case deprive a soldier of unavoidable disgrace and their fellow soldiers’ resentment.

The disgraceful punishments

Roman authors of the imperial era traditionally continued to praise the ancient tempers of such military leaders as Domitius Corbulo or Avidius Cassius. The latter was distinguished by legendary severity of his morals. According his biographer’s words, who lived, however, in a much later epoch,

“He flogged on a square or behead in the middle of a camp those who deserved it (…) He cut hands off deserters, to others, he broke the shins and popliteal cups and said that a left alive crippled criminal would serve a better example than killed one”.

According to a general belief of that time, peaceful life idleness and inactivity deadly influenced the military discipline, blowing up the moral and physical conditions of the soldiers. They believed that hard labour, constant physical training, long-lasting service in remote garrisons side by side with fierce enemies would be great means to keep in check the most troublesome units that otherwise would not be able to resist mutinies or crimes on their own.

Reconstruction by Graham Sumner

Along with that, especially in comparison to the predecessors, they began to value the moderation of those commanders who rather than to resort to any kind of repressions tried to solve problems with personal example and by means of conviction. The camp justice became much more flexible. For a minor offence a culprit was imposed by extra duties, he could be left beyond camp walls for a night or sent to a brig. Those who showed cowardice or disobedience could be made dig trenches, chop straw, carry bricks or fulfill any other hard and dirty work.

Disgraceful punishments became widespread among penalties at that time. At the same time, perpetrators were exposed in humiliating way, being ordered, for instance, to stay in the camp center barefooted, unbelted or being clad in the clothes cut from the top to the bottom, holding a measuring fathom or turf in hands. Those punishments were done in front of their fellow legionnaires’ eyes and appealed to their sense of honour and at the same time they were effective means of military discipline support in the ranks of professional army.

Sources:

- Makhlayuk, V.A. The Army of the Roman Empire. Essays on traditions and mentality / V.A. Makhlayuk. — Nizhny Novogorod, 2000;

- Makhlayuk, V.A. The soldiers of the Roman Empire. Traditions of military service and military mentality / V.A. Makhlayuk. — St. Petersburg: «Acre», 2006;

- Tokmakov, V. N. The military oath and «sacred laws» in the military organization of the Early Roman Republic / V. N. Tokmakov. // Religion and Community in Ancient Rome. Edited by: Kofanov L.L., Chaplygin N.A. — M.: Publishing House of the IVI RAS, 1994. — pp.125-147;

- Tokmakov, V. N. Sacred aspects of military discipline in Rome of the Early Republic / V. N. Tokmakov. // Bulletin of Ancient History. — 1997. — No. 2. — pp. 43-59;

- Mayak, I.L. The Romans of the Early Republic / I.L. Mayak. — M.: Publishing House of

- Moscow State University, 1993.