Even though the first battle of Narvik didn’t result in a complete victory for the 2nd Destroyer Squadron of the Royal Navy, the victory itself was significant. At that time, the Kriegsmarine had to decide what to do next.

The British faced the challenge of wiping out the remaining German ships. Late on April 10, 1940, vice-admiral William Jock Whitworth received an order from London to attack Narvik immediately with any forces-in-being, comprised of light cruiser HMS Penelope and several accompanying destroyers. It was also reported that the enemy had two light cruisers and at least six destroyers, which is why Whitworth decided to postpone the attack until reinforcements arrived.

The German ships remaining in Narvik had a more complex task to deal with—they had to return to Germany. Late in the afternoon of April 10, Captain Erich Bey, who had replaced the perished Friedrich Bonte, gathered all commanders of the destroyers on his flagship Z9 to discuss their plan of action. During the discussion they decided that they needed to perform a breakthrough with all combat-ready ships. This is what the group commanded, and this is what the naval high command insisted on. Bey gave the sailing order.

Only two ships were in a position to be able to do that immediately—Z9 Wolfgang Zenker and Z12 Erich Giese. The destroyers moored aside of the foundered supply ship Jan Wellem and started filling their fuel tanks. The other ships were undergoing emergency maintenance.

On April 10, at 19:40, Erich Bey sailed with two destroyers from Narvik to Ofotfjord and set a course for the west. At 21:05, the silhouettes of British ships were spotted on the horizon, Penelope and her destroyer escorts. Bey could not but notice the superiority of the enemy, so he refused to go ahead with the breakthrough, instead laying a smokescreen and retracing his course.

The next morning, two German ships were still being repaired and refueled. By the afternoon of April 11, Bey had 4 battle-ready destroyers: Z9 was joined by Z13 Erich Koellner, Z18 Hans Lüdemann, and Z19 Hermann Künne. Z12 was out of action due to engine failure. However, Captain Bey hesitated—he understood that the positive chances of breaking through these superior forces were still scarce. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were meant to cover the Narvik group on its return journey, but after the battle with battlecruiser HMS Renown on April 9 sailed somewhere to the north and went radio silent.

The extremely difficult navigating conditions of the Norwegian Fjords affected the plans of both parties. Shortly before midnight on April 11, Z13 ripped the bottom of her hull on the ridges in Ballangen: two boiler compartments were flooded, and four out of six boilers were disabled. Several minutes later, Z9 damaged her propeller blades by touching the seabed. The British were unfortunate as well. During the night of April 11, Penelope damaged her hull on the rocks, forcing her to sail all the way back home for maintenance.

In the morning of April 12, Bey had to set the idea of breaking through aside and started preparing for defense instead. He wanted to deal as much damage to the enemy as he could before his ships were destroyed. The fuel from the damaged Z13 was distributed amongst the other destroyers, leaving her only with a minimum amount. It was decided to berth the ship near Torstadt and use it as a floating battery. The heavily damaged Z17 Diether von Roeder was at the pier-side, with both guns still functioning, and was turned in the direction of the exit from the harbor. The rest of the ships were still being prepared for battle.

By the afternoon of April 12, the main forces of the Home Fleet, under the command of Charles Forbes, arrived to the Lofoten area with aircraft carrier Furious. Later on, Forbes gave the order to attack Narvik during the day on April 13. Whitworth transferred his flag to battleship Warspite and also took command of nine destroyers. In the evening of April 12, the aircraft from Furious raided Narvik. Due to poor visibility conditions, only nine aircraft were able to attack their targets, but at the same time they were able to bomb those targets effectively. Z13 received one direct hit, while three Norwegian patrol vessels captured by the German forces sunk along the way.

Z18 was sent to Ofotfjord to patrol at night. Bey correctly assumed that the enemy would attack in the afternoon of April 13. This reasoning is why the damaged Z13 left Narvik in the morning at low speed, accompanied by Z19, to take position near Torstadt. The latter was supposed to replace Z18 on patrol.

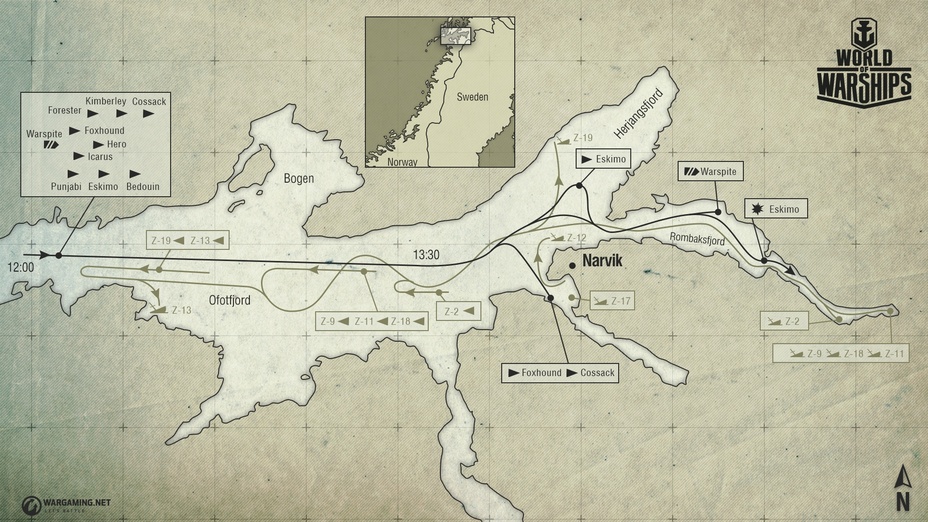

At around midday on April 13, the squadron under the command of vice-admiral William Whitworth entered Vestfjorden. The formation of the British ships was as follows: Cossack, Kimberley, and Forester along the northern shore of the fjord, Bedouin, Punjabi, and Eskimo—along the southern. They were followed by Icarus, Hero, and Foxhound, clearing the path for Warspite with minesweepers. In the apt words of Hero’s commander H.W. Biggs, the battle formation of the British squadron resembled a hunter with a pack of hounds in front of him. Warspite launched a scout aircraft for reconnaissance. At 12:03 it spotted Z19 and, at 12:10, Z13 was seen trudging towards their position. Later on, the aircraft scouted Narvik and its surroundings: spotting Z18 at the harbor entrance, and also spotting and sinking German submarine U64 in Herjangsfjord.

Z19 spotted the British ships at 11:56, and quarter hour later, they entered Ofotfjord. The destroyer gave the alarm and retreated, covered by a smoke screen. Z13, which wasn’t able to reach Torstadt, turned south and headed to Djupvik. In such harsh visibility conditions, the British were only able to come into contact with Z19 at 12:28, and at 12:30 Bedouin and Cossack opened fire from their maximum range. However, they soon ceased fire because they couldn’t see a thing.

Z13 managed to reach Djupvik, where she dropped anchor near the shore. But unfortunately for the Germans, she was spotted by the returning aircraft from Warspite. Bedouin, Punjabi, and Eskimo were warned about the enemy and turned their guns and torpedo tubes to the south in anticipation. At 13:09, the enemy opened fire from a distance of 18 cables. The barrage lasted for about 10 minutes, destroying the forward end of Z13 and setting the ship on fire. The destroyer’s commander Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs gave the order to abandon ship soon after. But not everyone followed his order—the 127 mm gun crew kept fighting. Then Warspite opened fire with her main battery. Six salvos were enough to turn the destroyer into a floating wreckage. Crew losses amounted to 31 killed and 39 wounded. The Germans who reached shore were taken prisoner by the Norwegians.

At 12:15 Erich Bey sailed to Ofotfjord aboard Z9 for the final confrontation. It was followed by Z11 and Z18, later joined by Z19. Z2 and Z12 stayed in the harbor, with a plan to leave it at 13:00.

In the sealed space of Ofotfjord, it was almost hand-to-hand combat. Maneuvering intensively, the destroyers, hiding in smoke screens and sleet showers, exchanged torpedo salvos and an immense amount of shells. The accuracy of fire, though, was quite low due to the poor visibility – they were effectively blind firing in the hopes of scoring a fatal hit. Cossack’s hull was damaged by several explosions that were set off right next to her. Bedouin was also heavily damaged, receiving several hits at her forward end, demolishing the 120 mm gun mount and crippling her freeboard. Z9 was able to fire torpedoes at Warspite but missed. The British battleship was moving behind the “pack of hounds” at 10 knots, shooting intermittently with her main battery. In the heat of the battle, the aircraft from Furious were continuously attacking the German destroyers, but they failed to hit their targets, and AA guns from Z11 and Z12 brought down two of the aircraft.

By 14:00, Z9, Z11, Z18, and Z19 had almost depleted their ammunition, and together with Z2 they were forced away from the entrance of Narvik harbor. Erich Bey ordered his forces to retreat to Rombaksfjord, with Z2 setting a smokescreen and covering the retreating destroyers. Z9 and Z11, which had neither shells nor torpedoes left, moved to the further side of the fjord, preparing to be scuttled. Z2 and Z18 still had some torpedoes left, so they took position in front of the Strømsnes passage—the narrowest part of Rombaksfjord.

The signalmen on Z19 missed the signal to retreat. The destroyer commander, Korvettenkapitän Friedrich Kothe, decided to move back to Herjangsfjord, run ashore, abandon the ship, and detonate her. The destroyer didn’t suffer any damage, there were no personnel losses, but her magazines and torpedo tubes were empty. The crew came ashore, flood holes were opened, and depth charges were readied to be detonated. But Z19 hadn’t gone unnoticed by the British: it was followed by Eskimo, and at 14:13 she launched a torpedo at it from a distance of 25 cables. The explosion broke the German destroyer into pieces.

Approximately at 13:50, when Bey and four destroyers started to move towards Rombaksfjord, Z12 was finally able to get underway. Her commander Karl Smidt faced a dilemma: whether to enter battle with a superior enemy, or to remain where he was, save the crew and scuttle the ship. To Smidt’s credit, he decided to accept the battle. On the way out of Narvik harbor, Z12’s port engine stopped, delaying the destroyer by a quarter hour. At that moment, from a distance of 30 cables, Bedouin and Punjabi opened fire on the German ships. The German gunners responded. Soon the distance was reduced to 15 cables. Punjabi took several hits, which forced her to retreat. Z17 received two hits and Z12 wasn’t damaged at all.

Finally, at 14:05, Z12 arrived at Ofotfjord but only to get under a devastating fire from Warspite. The destroyer launched a torpedo salvo at the battleship and opened fire with her artillery. When she ran out of shells, Smidt gave the order to abandon the burning ship, leaving it to drift in the middle of the fjord. The English kept firing and turned Z12 into debris even before she sank.

By 14:00 the battle was practically over, and the only thing left for the British to do was to finish off their weakened enemy. This is why, just after 14:00, a signal from the age of sail was sent: “The enemy must be destroyed immediately. Ram and board, if necessary.”

The British destroyers started to sweep the fjords, bays, and coves. At 14:15, Cossack, supported by Warspite’s artillery, rushed into Narvik harbor, where she immediately faced the accurate artillery fire from Z17, which had only enough shells left for 5 salvos. Over the course of this close quarters fire Cossack received four hits, disabling the rudder gear and engines and causing 9 casualties. The out-of-control British ship took to ground near Ankenes at 14:22. Cossack’s commander requested help from Kimberley, but her rudder gear was also damaged. Admiral Whitworth ordered Foxhound to enter the harbor and board Z17, thus helping Cossack. There was only half a cable’s length between to the German destroyer and Foxhound, when the charges on the former exploded at 15:20.

Rombaksfjord was the only place that wasn’t scouted by the British. Icarus, Forester, Hero, and Bedouin, led by Eskimo, rushed towards it. Eskimo’s commander, who had just sunk Z19, wanted more. Everything was looking good until Eskimo reached Strømsnes, where the fjord narrowed to only one cable. This is where Z2 and Z18 decided to make their last stand. Both destroyers launched torpedoes at the British destroyer and, even though the distance between them was very short, Z18 missed her shots. But the torpedo launched from Z2 hit Eskimo at 14:45. The resulting explosion tore off her fore-end, and the ship was dead in the water. The British destroyers that came to her aid opened fire at Z2 with all the guns they had, from main battery to AA machine guns, with the German destroyer only responding with occasional salvos. By 15:00, Z2’s magazines were empty, and her commander Korvettenkapitän Max-Eckart Wolff grounded the damaged ship, breaking it into two parts. The courageous resistance of the Germans delayed the British, which allowed Z18 to move deeper into Rombaksfjord and join Z9 and Z11. But their magazines and torpedo tubes were empty, and all the Germans could do was to scuttle their destroyers.

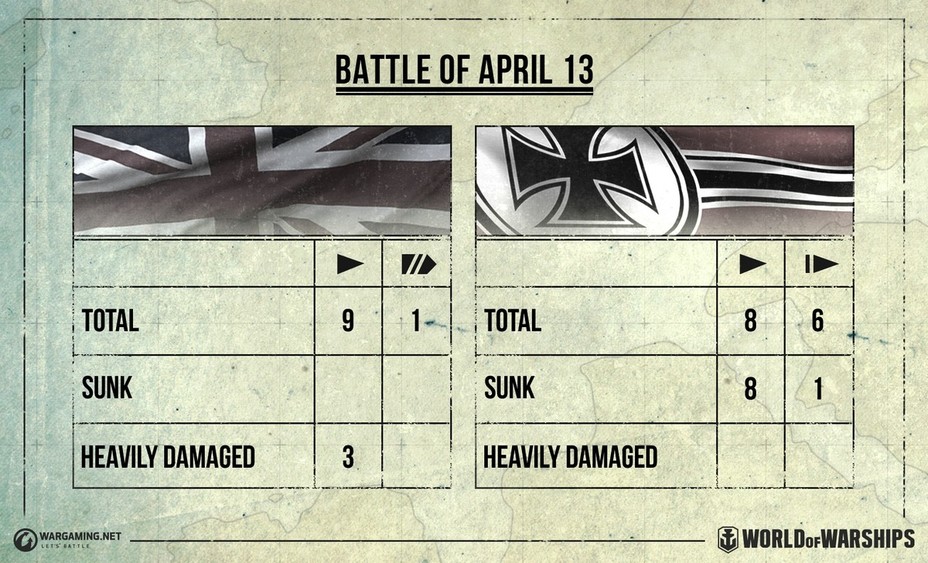

Having learnt from the previous experience, the British ships carefully moved towards Rombaksfjord’s head. There, they discovered the three blown-up German destroyers. Z9 and Z11 had already sunk and the boarding party was only able to step aboard Z18. The British hoisted the Union Jack over it and left the ship. Finally, a torpedo launched from Hero marked its fate decisively. The battle was over.

Vice-admiral Whitworth ordered his ships to gather at Vestfjorden. Kimberley and Ivanhoe, which appeared just in time, stayed near Narvik to cover the damaged Cossack. At night, Ivanhoe picked up the survivors from Hardy and British merchant ships that sank in the harbor near Ballangen—about fifty persons in total. By that time, Cossack had completed the necessary temporary repairs, but she was only able to float off the next morning, assisted by the tide.

This is how the Narvik saga ended for British seamen. For the Germans, it was just the beginning. The crews of the ships that sank formed a marine detachment comprising 2,600 men, that successfully fought side by side with general Dietl’s 3rd Mountain Division against the Allied forces in the surrounding region. The marine engineers also had their part to play—together with sappers they restored Narvik’s port, and repaired transport links, rolling stock, and armament.

The Battles of Narvik are a perfect example of the many practical applications of destroyers in naval combat. This series of engagements showcased the many dynamics of small-scale modern naval combat, including combined arms and anti-submarine warfare, as well as the tactical use of terrain and different weather conditions to seize the advantage. Historically speaking, this event held high significance: while prospects seemed bleak for the allied cause in 1940, the naval battles of Narvik would remind the world that Britannia still ruled the waves.