It's time to remember the most successful operation carried out by British destroyers in World War II. The attack caught Germans completely by surprise, while the British realized their tactical potential to the full extent. Frankly speaking, these events sound like they came from the pages of a novel, but it all really happened.

In April 1940, Germany began Operation Weserübung, aimed at occupying Norway, and which came as a big surprise for the British command. However, they quickly recovered from the shock of it and started actively opposing the Germans. In fact, their opposition was so intense that the German command came to the conclusion that the British were getting ready to launch their own operation to occupy Norway, within days.

It was impossible to counteract German troops in the southern regions of Norway because the entire area fell within the active range of the Luftwaffe. For this reason, the British Empire decided to strike back in Northern Norway. The town and port of Narvik was chosen for the counterstrike. Located far up North, Narvik appeared to be isolated from the main theater of hostilities and the Admiralty couldn't presuppose that the Kriegsmarine would allocate considerable forces to capture it. According to British intelligence, only one transport entered the port on April 9 and started unloading troops.

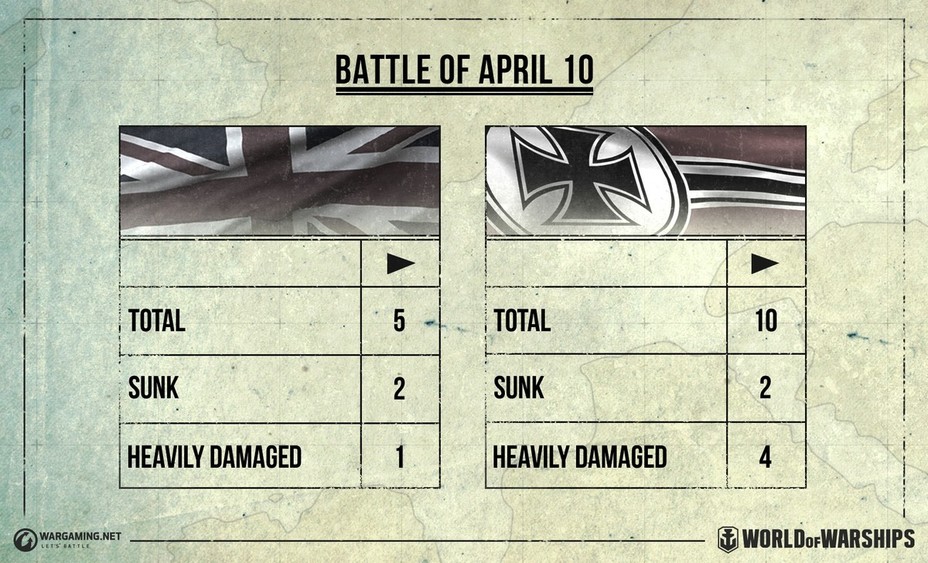

Based on this data, the Admiralty decided to attack the enemy in Narvik. The 2nd Destroyer Flotilla under Captain Bernard Warburton-Lee, cruising near the Lofoten Islands, was sent there. The flotilla comprised destroyers HMS Hotspur, Havock, Hunter, and Hostile and was led by flagship HMS Hardy. All of them were H-class destroyers carrying four 120 mm guns (only Hardy had five of them) and two quadruple 533 mm torpedo launchers; the ships could speed up to 35 knots and had the total displacement of 1,350 tons. The 2nd Flotilla was to enter the Vestfjord, proceed to Narvik, and destroy the enemy. The decision whether to land troops and liberate the city was the flotilla commander's to make.

What the Admiralty didn't know was that the «one transport» allocated to capture Narvik was in fact a joint Kriegsmarine squadron comprising ten destroyers from the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Flotillas under command of Commodore Friedrich Bonte, which served as troop transports in this operation. Having unloaded soldiers during the day, the destroyers planned to leave Narvik by nightfall on April 9, but their fuel tanks were virtually empty—with uneconomic engines playing a role in this. The issue was even worse because one of the two tankers attached to the destroyers was intercepted and sunk by Norwegians, and the remaining Jan Wellem wasn't able to refuel more than two destroyers at once. The departure was postponed until the evening of April 10.

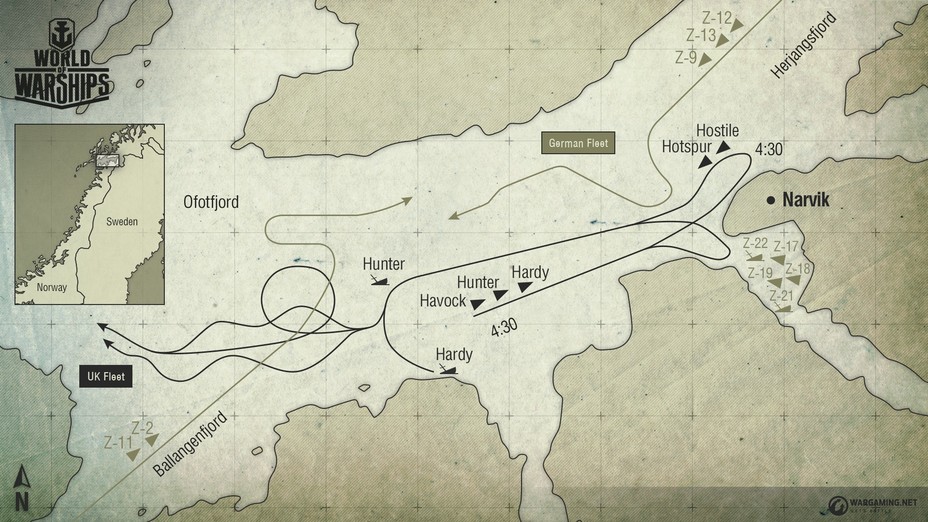

Bonte dispatched three destroyers with a small fuel reserve to keep the night watch: Z-17 Diether von Roeder was to patrol the entrance to the Ofotfjord, while Z-2 Georg Thiele and Z-11 Bernd von Arnim dropped anchor at the Ballangenfjord ready to exit if necessary. The remaining seven ships moored further in the fjord: Z-21 Wilhelm Heidkamp, Z-22 Anton Schmitt (Bonte's flagship), Z-19 Hermann Künne, and Z-18 Hans Lüdemann were in the port of Narvik and the latter two were in the process of refueling. Z-12 Erich Giese, Z-9 Wolfgang Zenker, and Z-13 Erich Koellner dropped anchor at the Herjangsfjord. That was the disposition of German ships during the night and morning of April 10.

On April 9, the British 2nd Flotilla entered the Vestfjord. At a pilot station Warburton-Lee received fresh but incomplete information about the adversary—at least six destroyers had sailed to Narvik and, apart from this, the Germans had most probably mined the approaches to the port. Warburton-Lee communicated the obtained data to the Admiralty and received an answer that he needed to take the decision about the attack on his own, depending on the situation. Early in the morning of April 10, a radiogram was sent from the 2nd Flotilla's flagship—«I'm going to attack at dawn."

To understand the difficulty of the task at hand, you need to remember that the German destroyers belonged to types 1934 and 1936 and were significantly larger and more powerful than the British ones: their displacement was between 2,200 to 2,400 tons, speed—up to 38 knots, armament—five 127 mm guns and two quadruple 533 mm torpedo launchers.

At 03:00 the 2nd Flotilla began to move up the fjord. Destroyers formed an echelon right formation to give all the ships the ability to fire along the course. General quarters was sounded at 04:15. The weather contributed to the success of the British plan—a windsquall with heavy snow and visibility of only 2 cables. The attack caught the Germans completely by surprise. Although, it's worth noting that there was a part of their fault in it. Owing to a misunderstood order, the captain of Z-17— Korvettenkapitän Erich Holtorf—believed that if there were no incidents during the night, his orders were to end at dawn. Afterwards, he could leave his patrol area at the entrance to the Ofotfjord and return to the temporary base. The destroyer sailed back to Narvik and dropped anchor in the harbor at 04:20.

At 04:30, the British destroyers burst into the harbor. Hardy was leading Havock and Hunter, while Hotspur and Hostile stayed in the immediate rear in case there was the necessity to suppress shore batteries. However, they quickly understood that there were none and joined their comrades within several minutes.

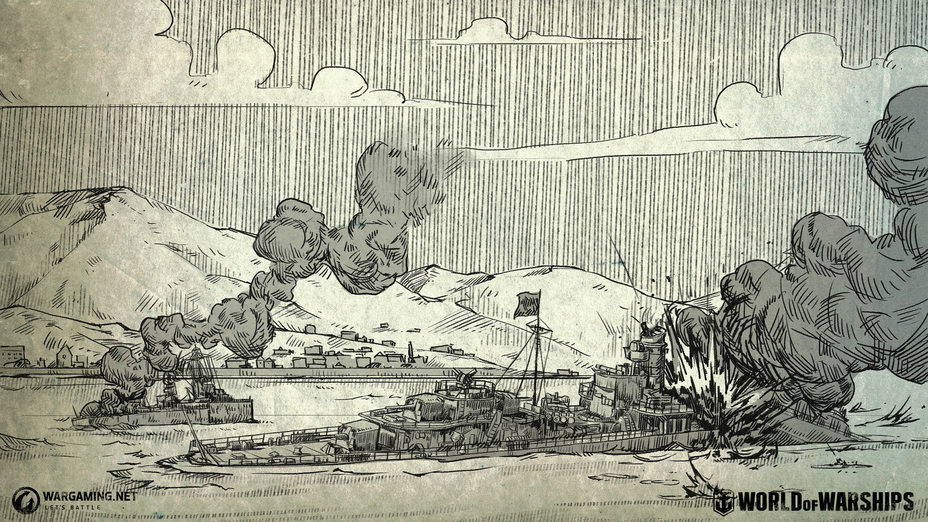

From five German destroyers the British spotted only two—Z-21 and Z-22. The British ships immediately launched torpedoes and opened artillery fire at them. At 04:35, a torpedo from Hardy struck Z-21's stern. The ensuing detonation of the ship’s magazines and its own torpedoes devastated the entire aft of the destroyer. Z-22 was hit by two torpedoes from Hunter and the German was torn in two. Z-19, moored to the tanker, was tossed up by explosions with such force that her turbines were moved from their foundation and disabled.

The onslaught came as a complete surprise for the Germans—their first thought was that they were being attacked by aircraft. They noticed the British destroyers several minutes later. Artillery from Z-17, Z-18, and Z-19 returned fire, but without any results. Z-17 launched torpedoes, but they passed under the British ships because of damaged diving rudders.

The destroyers from the 2nd Flotilla were more accurate: Z-18 had her steering gear damaged and the ensuing fire forced her crew to flood the aft magazine. Z-17 was simply straddled at point-blank and Korvettenkapitän Holtorf had to steer his ship to quay and evacuate the crew.

The British destroyers laid a smoke screen and fell back to prepare a second attack. During their second approach, lasting around one hour, the British set out to sink the merchant vessels. Jan Wellem, with much-needed oil in her cargo holds, was among the sunken ships.

In this attack all five German destroyers were either sunk or heavily damaged; around 150 sailors lost their lives, including Commodore Bonte. Captain Warburton-Lee had every reason to be satisfied with the results: the British destroyers were unharmed and began their retreat. Z-18 launched four torpedoes after them, but fruitlessly.

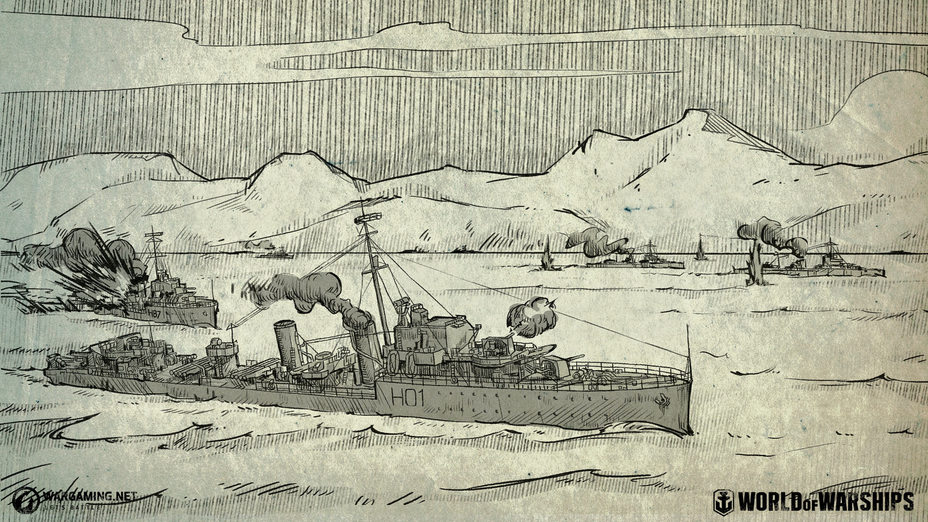

However, it wasn't the end of the battle. Three German destroyers emerged from the mist on their starboard side and opened fire from a distance of 35 cables—those were Z-9, Z-12, and Z-13 under Kapitän zur See Erich Bey. However, they had to cease fire for a short time to dodge the torpedo spread launched by Z-18. At the same time, Z-11 and Z-2 emerged from the Ballangenfjord and found themselves directly in front of the British ships, thus cutting the 2nd Flotilla off their exit to sea. It was then that luck turned its back on the British: for some reason, Warburton-Lee decided that these ships were reinforcements from the Royal Navy, and he paid a high price for this mistake.

At 06:57, Z-11 and Z-2 opened heavy fire on Hardy that was in the lead and, having cut the forward part of the enemy flotilla, they exchanged fruitless torpedo salvos with Havock. By that time, the three destroyers commanded by Bey were finally able to approach to attack distance and opened fire on Hardy. The crossfire from the German ships quickly turned the British flagship into a burning ruin. A downpour of shells destroyed the bow superstructure and disabled its machines. Captain Warburton-Lee was mortally wounded and turned command over to Lieutenant Stanning. They lost control of the ship and were losing speed, and it had to be beached in the southern part of the Ofotfjord. Following their flagship's destruction, Commander Herbert Lyman assumed command of the 2nd Flotilla.

The British returned fire and scored seven hits on Z-2. In reply, the German destroyer launched three torpedoes, with one of them striking Hunter. The latter abruptly slowed down, while being subjected to heavy shelling. At that moment, the out of control Hotspur rammed into Hunter due to her steering gear being disabled by enemy fire. The coupled ships made a tempting target for the approaching Z-9, Z-12, and Z-13.

The situation was salvaged by the captain of Havock, Lieutenant Commander Reif Courage. He turned his ship around, and together with Hostile that followed him, charged at the Germans, simultaneously setting a smoke screen to cover the virtually immobilized Hunter and Hotspur. The maneuver was a success— the Germans ceased the pursuit. Hunter was sinking and beyond help. Havock and Hostile sailed towards the Ofotfjord's exit. Hotspur also left, steering with her machines.

Erich Bey refused to chase the retreating enemy and the Germans paid a high price for this decision by the 4th Flotilla commander. At the exit of the Ofotfjord, the British received a «consolation prize»—they managed to sink the supply ship Rauenfels, sailing towards Narvik with a cargo of shells and torpedoes for the destroyers.

At the mouth of the Ofotfjord, the battered ships from the 2nd Flotilla rendezvoused with their reinforcements—a squadron commanded by Captain Yates consisting of cruiser HMS Penelope and destroyers HMS Bedouin, Eskimo, Punjabi, and Kimberley. The misadventures of the 2nd Flotilla were over for the day…

Bernard Warburton-Lee and Friedrich Bonte were posthumously awarded the highest military awards of their countries for this battle: the Victoria Cross and the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross accordingly.

But that's not all! Don't miss the continuation of the story!