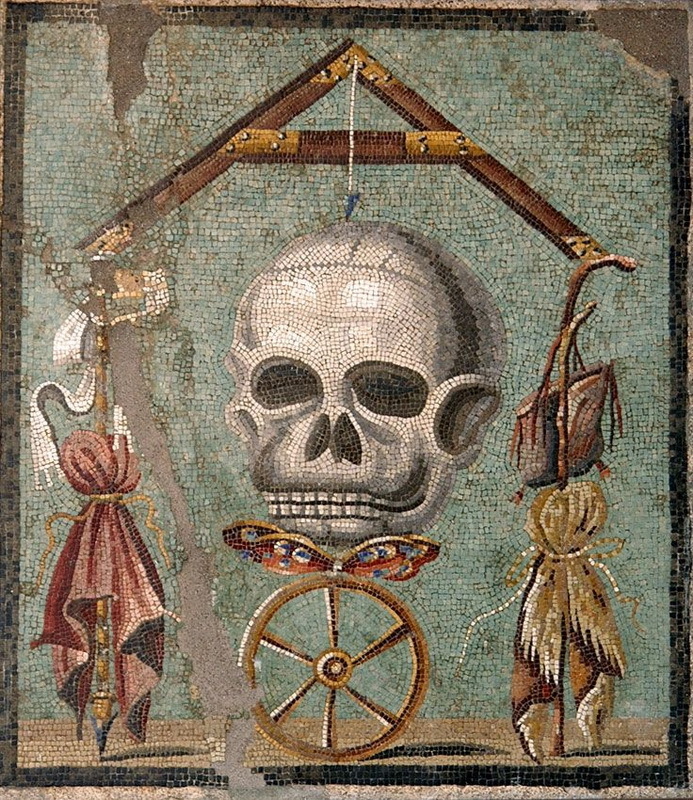

To date, some 200 distinct concepts have sought to account for the fall of the Roman Empire. Researchers traditionally emphasize political, military and socio-economic aspects. In recent decades, however, scholars have increasingly been looking at the problem from a different perspective, focusing more on climate change and related disease outbreaks. Now that the world has changed a lot in just a year and a half thanks to the China-born coronavirus, we recollect the greatest epidemics of antiquity, which effectively put an end to the power of the Roman Empire and dipped the world into the Middle Ages.

The End of the Golden Age

The 1st and 2nd centuries saw the heyday of the Roman Empire. At that time, it encompassed a vast territory from Upper Egypt to Northern Britain and from Mesopotamia to the Atlantic coast. Its borders were more than 10,000 kilometers long, and based on prevailing estimates, it had a population of approximately 65 million people, which at the time accounted for a quarter of all human beings. The Roman state had a sophisticated structure and incorporated numerous social groups and territories with varied political structures, social orders, economies, ways of living and cultures. The provinces were involved in intense trade relations through a comprehensive system of roads and navigable routes. According to modern historians’ estimates, the Roman Empire’s GDP could have reached $93 billion, which is comparable to the European living standard of the eighteenth century. No wonder the English historian Edward Gibbon referred to the rule of the Antonines as the happiest age of mankind. However, the heyday of Roman civilization already featured preconditions for its future decline and demise.

en.wikipedia.org

The decline of the Golden Age of the Antonines marked the end of the Roman climatic optimum, which spanned from about the second half of the 3rd century B.C. to the beginning of the 5th century A.D. During that interval, the Mediterranean climate was the warmest, dampest, and most stable in the previous several thousand years. Average temperatures were probably identical to those we observe now or were even 1–2 °C higher. Archaeological evidence suggests that areas under crops included lands that are currently deep into the desert. Around the middle or second half of the 2nd century, a period of climatic change started in the Mediterranean, which caused the weather to become a lot drier and cooler over the following 50 years. Those changes, although not fatal, brought about certain disorder to Roman society. Even in the most fertile provinces of the empire, harvests became poorer, causing food prices to hike, trade to decline, and price inflation to develop.

The Antonine Plague

The most painful blow to the well-being of the Roman society of the Golden Age came from an epidemic of a mortal disease. The ancients themselves considered it a plague (λοιμος), but in reality it must have been smallpox. The pestilence is believed to have emerged and spread in connection with the events of the Parthian War of 161–166. The first cases of infection were recorded during the conquest and pillage of Seleucia on the Tigris by Romans in the winter of 165–166. In the spring, the losses suffered by the Roman army were such that the offensive in Media, which had started quite successfully, had to be cancelled and the troops had to return to their bases. That decision by commanders turned out to be fatal: the soldiers returning from the campaign brought the infection into the empire. It soon spread from Syria to Asia Minor and from there, through the densely populated cities of Smyrna, Ephesus, and Athens, to Greece and all over other provinces. Owing to the evolved roads and navigation, the epidemic soon reached the remotest and most forbidden regions of the empire.

pinterest.ch

Data on the clinical features of the epidemic are scarce and scattered. Their main source is the notes made by the famous Roman physician Galen. For this reason, the Antonine Plague (named after the emperor Marcus Aurelius, during whose reign it occurred) is also known as the Plague of Galen. Galen was in Rome in 166 when the first cases of the disease were reported there, and then observed repeated outbreaks in Aquileia in 168–169 and subsequent relapses. Galen attributed the disease to an imbalance of internal body fluids and was convinced that the sickness could be cured by removing excess fluid from the body through rashes and blisters that appeared on a patient’s body on the ninth day of the illness. In the fourth volume of his treatise The Art of Medicine, Galen wrote that if the rash was accompanied by purulent blisters, a patient had a hope to be cured. Otherwise the case was lethal. Other symptoms of the disease indicated by Galen were fever, vomiting, gastrointestinal problems, diarrhea, bad breath, and cough.

The consequences of the epidemic proved to be a disaster for the population of the Roman Empire. Between 166 and 169 about a quarter of the personnel of the eastern legions and about a fifth of the Danubian army died of it. When it comes to the civilian population, the largest metropolitan areas with hundreds of thousands of residents were hit the hardest. In Rome, according to Cassius Dio, the disease took the lives of about 2,000 people a day, and every fourth of those infected died. In Spain, entire regions were decimated: their populations either died out or fled to save their lives. Tax lists from Egypt paint a picture of mass deaths and the exodus of survivors to remote areas. Studies by Richard Duncan-Jones and Yan Zelener show the mortality of the epidemic at between 25% and 33% of the total population of the empire. Robert J. Littman offers more moderate figures: an average of 7–10% with peaks exceeding 15% in urban areas. Therefore, in 166–189, the epidemic claimed lives of between 7 million and 10 million people.

pinterest.co.uk

Plague of Cyprian

At the beginning of the 3rd century the situation stabilized. In the wake of climatic improvements, the economy began to recover, and a slow yet consistent growth of population followed. But those new figures never reached the level of the Golden Age. In the middle of the century, a new cold spell came, which coincided with another wave of the epidemic.

The disease was first manifested in Ethiopia during the Easter of 250. From there the contagion quickly reached Egypt, moved on to Greece, spread to Rome, and finally to most of the provinces, where it raged for a decade. The epidemic went down in history as the Plague of Cyprian, its name commemorating St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, who witnessed the plague and described it in his treatise, The Book of Mortality. It appears that the disease was actually smallpox, virulent influenza, or a hemorrhagic fever similar in its progress to Ebola:

“This trial, that now the bowels, relaxed into a constant flux, discharge the bodily strength; that a fire originated in the marrow ferments into wounds of the fauces; that the intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting; that the eyes are on fire with the injected blood; that in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction; that from the weakness arising by the maiming and loss of the body, either the gait is enfeebled, or the hearing is obstructed, or the sight darkened…”

commons.wikimedia.org

Between 250 and 262, the pestilence wiped out the population of most of the major cities of the empire. In Rome, up to 5,000 people would die on a single day. Emperor Hostilian, who died in November 251, was a notable victim of the epidemic. Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, wrote that almost no people aged over 40 were left in the city, although there used to be many of them. The population of the city may have more than halved at that time. Pontius of Carthage, the biographer of St. Cyprian, described deserted streets, piles of dead bodies lying around, and townsfolk who strayed away from contact with their families or fled the city in terror. Cyprian himself encouraged his flock to keep their spirits up and even in those dire days not to neglect their last duty to the dead:

“Do we not see the rites of death every day? Are we not witnesses to its most bizarre forms? Do we not see the unprecedented calamities brought about by a disease unknown before?”

commons.wikimedia.org

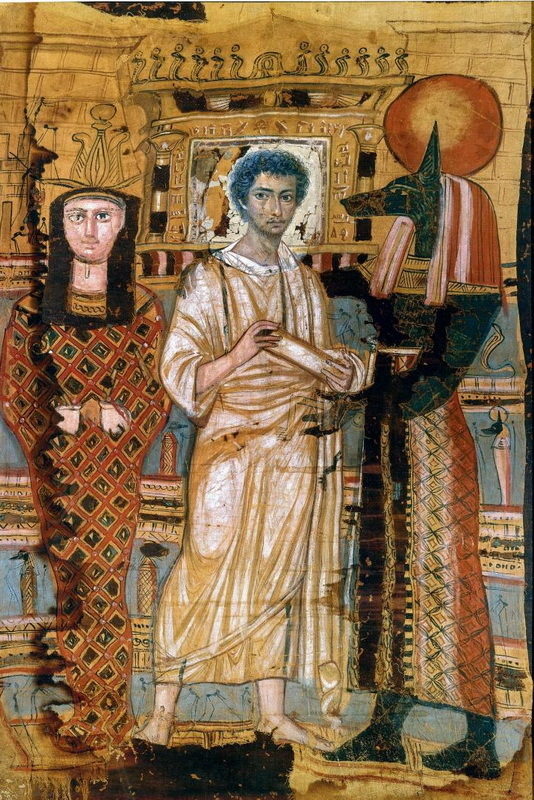

During the excavations undertaken between 1997 and 2012 at the Akhimenru funerary complex on the western bank of the Nile near present-day Luxor, a team of Italian archaeologists discovered a mass grave. The bodies were packed in pits and covered with a thick layer of lime, which was used as a disinfectant in ancient times. The usual signs of burial rituals were missing. Three lime kilns and a giant fireplace containing human remains were discovered here. Ceramic fragments dated those finds to the mid-3rd century and connected the burials with the victims of the epidemic. Because of the large number of victims, there was no time for proper burials, and bodies were either burnt or stacked under a thick layer of lime. This seems to have given the location a bad reputation and when the disease abated, no more burials were performed at the site.

pinterest.com

The Justinian Plague

The first recorded pandemic of bubonic plague, which swept across the continent from east to west and brought about unprecedented devastation, the Justinian plague, became an even more horrific calamity. The first cases of infection were recorded in Pelusium, Egypt, in 541, during the reign of Emperor Justinian I. Rats carried the disease all the way to Constantinople on ships with grain. The plague quickly spread from the empire’s capital along maritime trade routes to all of the shores of the Mediterranean, including Italy, Africa, and Spain. Across the Alps, the disease made its way to Gallia, then to Germany, and then crossed the Channel to get to Britain and Ireland. Its eastward progress was just as swift, devastating Syria and Mesopotamia in a matter of few years. The epidemic was at its apogee around 544, when it killed up to 5,000 people every day in Constantinople alone. The historians Procopius of Caesarea and Evagrius Scholasticus offer vivid descriptions of the disease:

“The misfortune was composed of different ailments. For in some it began with the head, making eyes bloodshot and face swollen, went down to the throat, and dispatched the victim from among men. In others a flux of the stomach occurred. While in some buboes swelled up, and thereafter violent fevers; and on the second or third day they died, with intellect and bodily constitution the same as those who had suffered nothing. Others became demented and put aside life. And indeed carbuncles sprang up and obliterated men. And there are cases where men were afflicted once or twice and escaped, but perished when afflicted again. And the ways in which it was passed on were various and unaccountable. For some were destroyed merely by being and living together, others too merely by touching, others again when inside their bed-chamber, and others in the public square. And some who have fled from diseased cities have remained unaffected, while passing on the disease to those who were not sick. Others have not caught it at all, even though they associated with many who were sick, and touched many not only who were sick, but even after their death. Others who were indeed eager to perish because of the utter destruction of their children or household, and for this reason made a point of keeping company with the sick, nevertheless were not afflicted, as if the disease was contending against their wish. So then, as I have said, this misfortune has been prevalent up to the present for 52 years, surpassing all previous ones.”

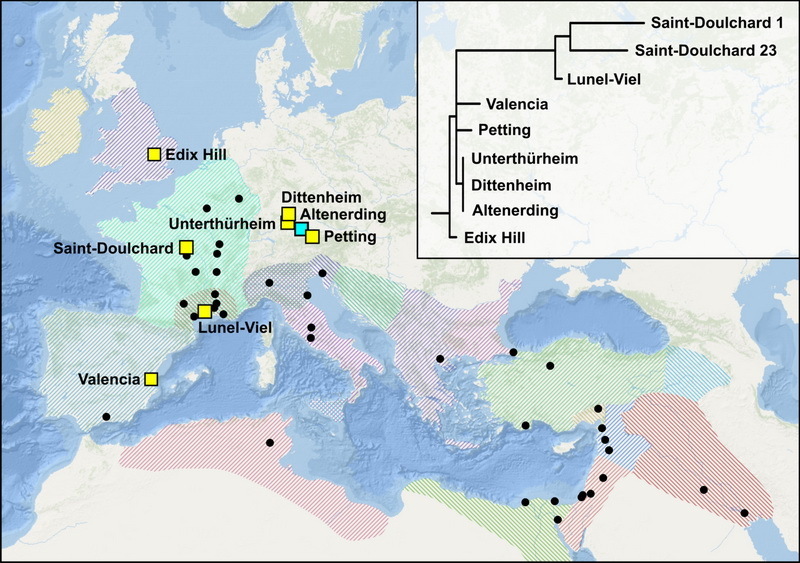

pinterest.com

The plague ravaged Europe for more than 200 years, between 541 and approximately 767, coming in 20 successive waves at 9–13-year intervals. The paths of the disease were mainly associated with sea and land trade routes, migration or military campaigns. In the West, following the first few waves, the expansion of the disease over land was checked within certain boundaries — unlike the Black Death in Europe in the 14th century. The actual spread of the epidemic in the sixth and seventh centuries was limited to the area with a high level of urbanization and intensive trade, i.e. the Mediterranean coast and adjoining traffic arteries such as the river Po in Northern Italy or the Rhône-Saône axis in Southern France. In the north, the valley of the Loire and the upper Rhine region became the border of the pandemic. There is no plausible explanation why the epidemic ceased two centuries after it began or how it disappeared from Europe. The depopulation of areas devastated by the disease or decreased virulence of the pathogen are probable yet insufficient reasons.

shh.mpg.de

According to the most conservative estimates, up to 100 million people worldwide became victims of the epidemic, whereas in Europe, it killed about 25 million people. The population of major cities, including Constantinople, Alexandria, Carthage, and Antioch, at least halved. The most economically developed coastal areas suffered the most, because of the high level of urbanization and concentration of population in major cities. Many rich and formerly developed agricultural areas lost a significant portion of their population and became desolate. The plague therefore was one of the main causes of the decline and death of the ancient urban civilization, which was already severely weakened by the war and economic turmoil of the preceding time.

shh.mpg.de

In 2014, scientists were able to confirm that the plague bacterium (Yersinia pestis) served as the causative agent of the deadly disease. Researchers managed to isolate it from the remains of victims of the epidemic found during the dig of an early medieval cemetery in Aschheim near Munich (Bavaria). The same bacterium caused the Black Death epidemic that decimated the population of the continent in the 14th century. Both bacteria were of Asian origin, but belonged to different strains. According to analyses, the strain that caused the Justinian Plague had either disappeared or become so rare that it is not identified in modern natural reservoirs of the disease — unlike the Black Death strain, whose descendants caused an outbreak of the Asian Plague at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. They are still found in wild rodent populations, which are natural reservoirs of the disease.

Sources:

- Harper, K. Plague, climate change and the decline of the Roman empire / K. Harper. — Princeton: University Press, 2017.

- McNeill, W.H. Plagues and Peoples / W.H. McNeill. — New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1976.

- Rosen, W. Justinian’s Flea. The First Great Plague and the End of the Roman Empire / W. Rosen. — Oxford: Penguin Books, 2007.

- Lester, K. Little Plague and the End of Antiquity. The Pandemic of 541–750 AD / K. Lester. — Cambridge: University Press, 2008.

- Gilliam, J.F. The Plague under Marcus Aurelius / J.F. Gilliam // American Journal of Philology. — 1961. — Vol. 82. — Р. 228–251.

- Littman, R.J. Galen and the Antonine Plague / R.J. Littman, M.L. Littman // American Journal of Philology. — 1973. — Vol. 94. — P. 243–255.

- Duncan-Jones R.P. The impact of the Antonine plague / R.P. Duncan-Jones // Journal of Roman Archaeology. — 1996. — Vol. 9. — Р. 108–136.